Summary

Early in the AM hours of February 25, 1942, the U.S. Army ordered a blackout of Los Angeles, California, and the surrounding areas in response to intelligence and radar reports that an unidentified enemy craft, presumably Japanese, was approaching. The U.S. was a few months into WWII, and the West Coast was on edge with the recent attack on Pearl Harbor.

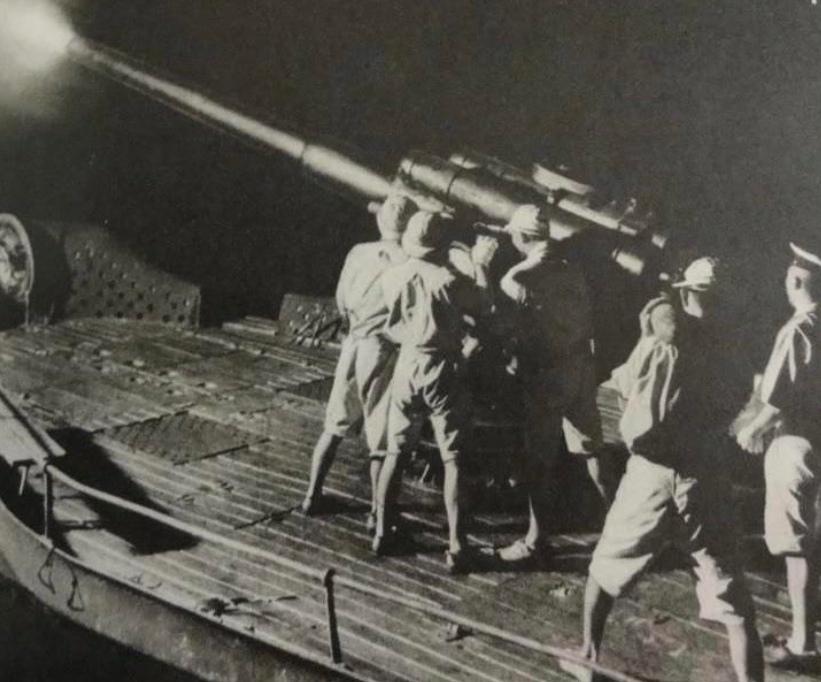

At about three AM, an unidentified aerial object was reported over the darkened city. Powerful searchlights raked the sky, and batteries of anti-aircraft cannons and machine guns opened fire, lobbing thousands of rounds over Los Angeles.

From the ground, some civilians and soldiers saw planes, others saw a dirigible or a balloon, and many saw nothing. The searchlights, however, seemed to track a large, slow moving object unfazed by the immense firepower trained upon it.

In the following days, the divergence of accounts deepened; U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson said that enemy planes had indeed flown over Los Angeles, whereas Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox said the episode was a “false alarm.”

Los Angeles emerged from the “battle” with a few incidental casualties and some property damage from the shrapnel that the Army’s exploding shells rained upon the city. The Japanese American community, however, suffered greater damage. Within a few months, the U.S. Government incarcerated virtually all West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry into internment camps.

In the decades following, as the UAP phenomenon emerged, some researchers began to speculate that a “flying saucer” or some non-human aircraft had been at the convergence of the searchilights. Despite many thousands of eyewitnesses, radar data, military engagement and investigation, the alleged enemy target at the center of the so-called “Battle of Los Angeles” remains unidentified.

Fear on the West Coast

December 7th, onward …

On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor near Honolulu, Hawaii. The attack not only triggered the U.S. entry into WWII, but also an acute fear that the West Coast would be next to face an onslaught of Japanese planes and ships.

Indeed, two nights later, reports came in of a Japanese aircraft carrier near San Francisco. Soon, radar detected incoming aircraft, and the U.S. Army ordered a blackout to shroud the San Francisco Bay Area from bombers and fighter planes.

No attack materialized, and on the following day, the press criticized General John DeWitt, who headed the military defense of the western U.S., for overreacting.

“You people do not seem to realize we are at war," DeWitt told reporters. "So get this: Last night there were planes over this community! They were enemy planes!"¹

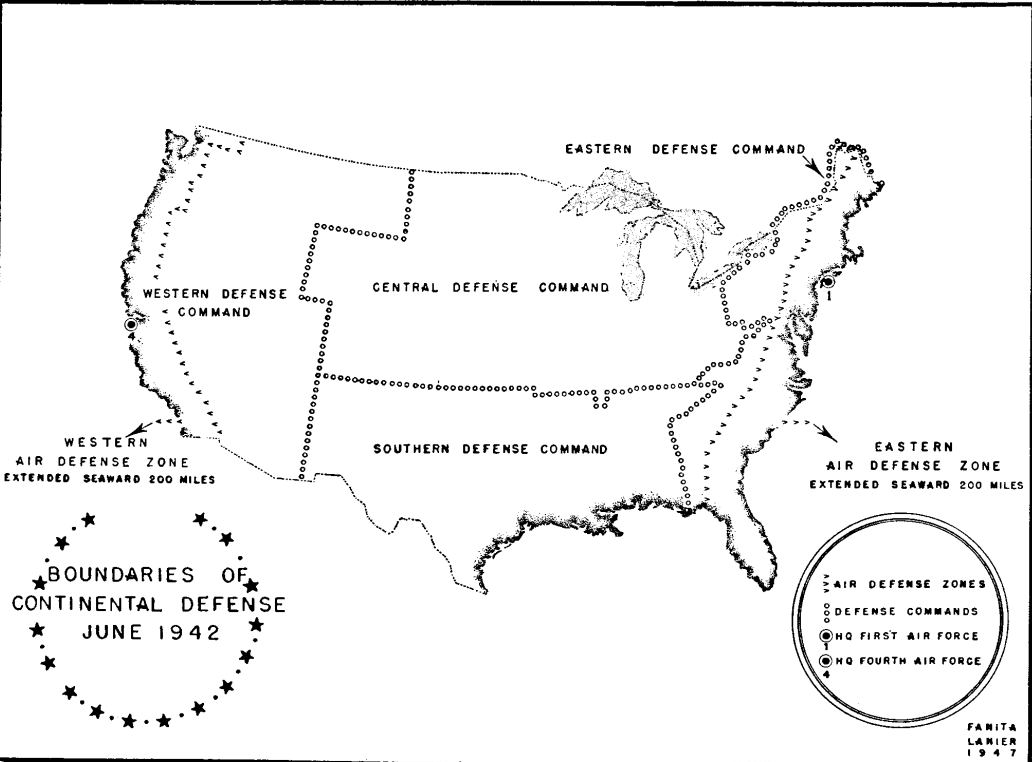

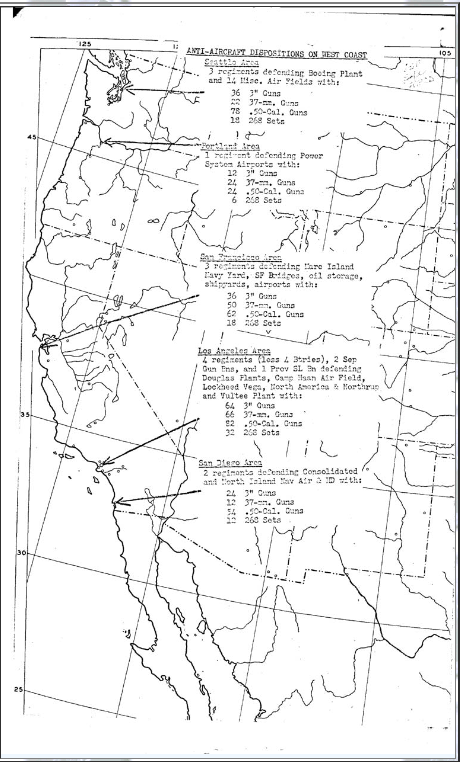

At the time, the U.S. military reckoned that Japan had the capacity to cripple the Panama Canal and establish bases in Alaska, Hawaii, Canada and Mexico, all to bolster an eventual invasion.² On December 11, anti-aircraft military units up and down the West Coast began training civilians to serve as air raid wardens and to surveill the sea and sky from observation posts, looking out for planes, submarines and aircraft carriers.³ In the Los Angeles-area, tens of thousands volunteered.⁴

The night before

Sub attack near Santa Monica

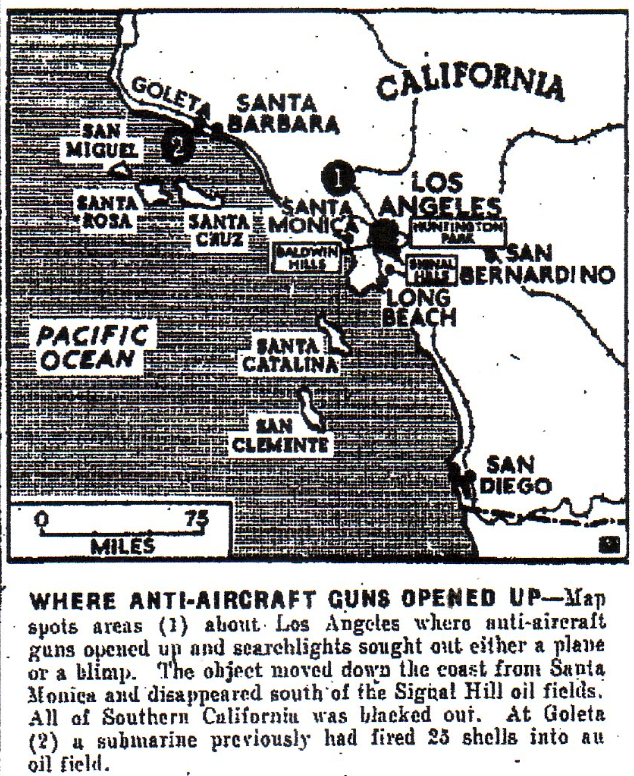

On Monday, February 23, 1942, at dusk around 7:15 PM, a submarine surfaced some 2,500 yards off the beach by the Ellwood oil field a dozen miles north of Santa Monica, California.⁵

The submarine, later identified as Japanese Imperial Navy submarine I-17, fired 13 to 16 shells from its 14cm/5.5-inch diameter gun at the oil field over the course of about 20 minutes. The likely target was Ellwood’s gasoline plant, the Army said, a critical facility for the region’s defense.⁶

The shells destroyed some rigging and pumping equipment, a five-foot stretch of dock, but otherwise went off target, hitting the water, the beach, or in one case, a field three miles inland.

“Their marksmanship was rotten!” a local innkeeper told the Los Angeles Times.⁷

The Los Angeles Times initially reported several thousand dollars in damage, but lowered that estimate to $500 the following day. No one was hurt. About half of the shells were duds, according to a U.S. Army investigation.⁸

Nevertheless, the attack occasioned the first Axis shells to hit the continental U.S., ratcheting fears of invasion. As Life magazine put it, “The murderous enemy was not separated from [California] by 5,000 oceanic miles, but only by a few feet of salt sea water, a few feet of dark night air.”⁹

That same week, General John Dewitt had recieved reports of escalating sabotage and word from Japanese informants that a bombing attack would occur within days.¹⁰

The night of …

The warning

According to the U.S. Army’s Fourth Anti-Aircraft Command, at 7 PM on February 24, almost precisely twenty-four hours after the Japanese I-17 shelled Ellwood, Naval Intelligence advised that an attack on the Los Angeles area would occur within ten hours. Reports came in that enemy agents were signaling with flares in the area’s hills. The Army placed a 460-mile stretch from the Mexican border to Monterrey on yellow alert, alerting the coastal defenses.

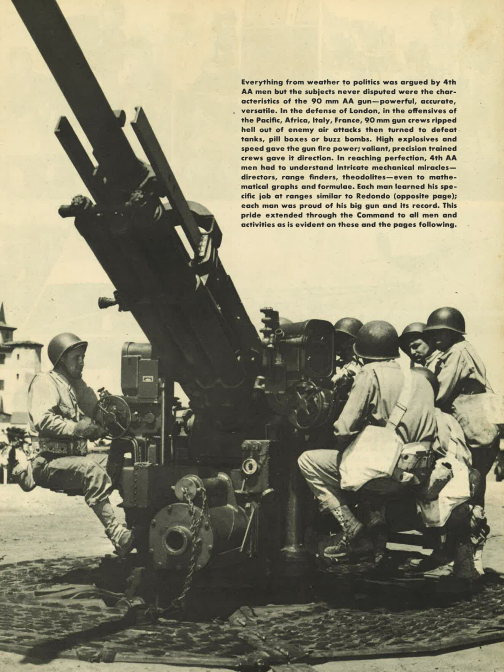

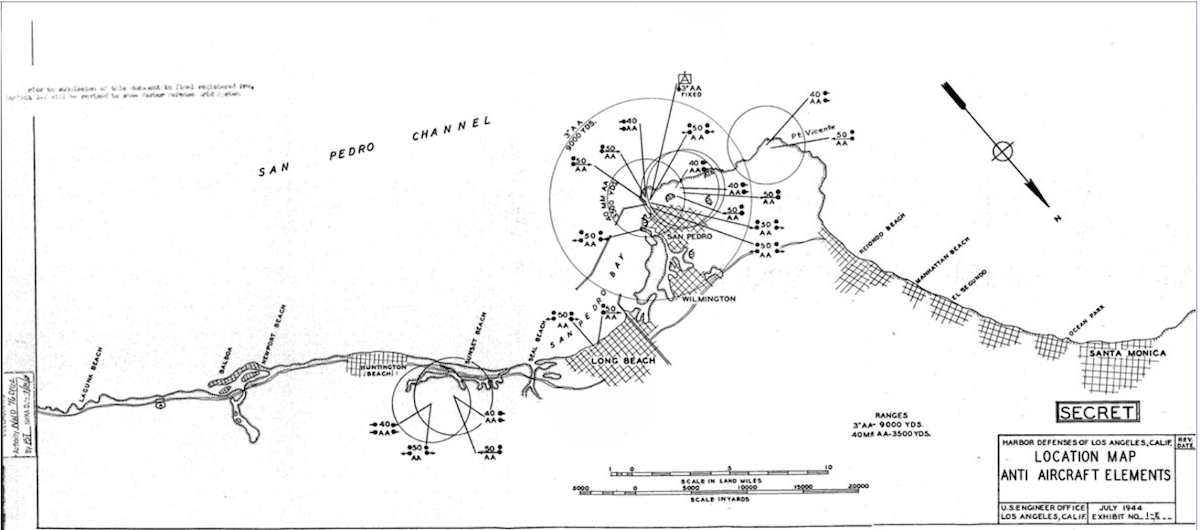

The Army and Navy had approximately 9,000 soldiers between four anti-aircraft regiments stationed in and around Los Angeles and over 200 anti-aircraft guns that ranged from cannon batteries with explosive shells to machine gun stations equipped with plane-piercing bullets.¹¹

The yellow alert lifted at 10:23 PM, but a few hours later at 1:44 AM on February 25, an SCR 268 radar picked up an unidentifiable target 120 miles off the coast of Los Angeles. Two SCR 270s, a newer generation of radar with a longer range, confirmed the target and its approach. At 2:21 AM, the “Region Controller” called for a blackout, and within minutes sirens wailed across the Los Angeles-area.

With the sound of the sirens, about 10,000 volunteer air raid wardens went to work. Wearing white armbands and whistles around their necks, their job was to see that every light visible from the outside was off or covered, that all drivers pulled over, shut off their headlights and went inside for shelter, and that everyone kept phone lines clear for emergencies.

Radar tracked the target within three miles of Los Angeles, which, given early readings would indicate an average speed of 200 miles per hour; fast for a bomber, slow for a fighter plane. At 3:06, a balloon carrying a flare was spotted over Santa Monica. Firing began.

Searchlights, tracers, shells

Over the next hour, the alleged target crossed over the Los Angeles area. Tracked by over a dozen immensely powerful searchlights, the target appeared to travel from north of the city by Santa Monica, crossing inland toward the Huntington Park area, then turning south and heading out over the ocean at Long Beach. At times the alleged target moved as slowly as ten miles per hour, as though trapped in the bright disc of the searchlights’ point of convergence.¹²

Joining the searchlights were thousands upon thousands of high caliber bullets, every fifth one a tracer that streaked the sky with golden yellow, and shells that exploded in bright flashes, sending out shrapnel and smoke. With all the noise and light, witness accounts of the target, or targets, diverged wildly.

Confusion in the streets

An air raid warden in Gardena, south of Los Angeles, reported a large balloon. A police officer named Carl Zeiss stood on the roof of Long Beach City Hall with binoculars and spotted nine “silvery” planes. His chief, J.H. McClelland, standing beside him, saw nothing. Minard Fawcett of Redondo Beach counted 15 planes, but thought better of it and determined they were reflections in the drifting smoke.¹³

Reporter Ernie Pyle, who had covered Germany’s bombing of London, watched the searchlights join into “a big blue spot in the heavens” but saw nothing in it.¹⁴ Closer to the target, men firing machine guns from the roof of the Los Angeles Civic Center saw a balloon or dirigible in the lights, though others among them with scopes and binoculars saw nothing.

Another reporter, Marvin Miles, saw multiple objects caught in the lights.

“It’s a whole squadron!” someone nearby said, according to Miles.

“No, it’s a blimp. It must be because it’s moving so slowly,” said another.

“I hear planes,” the first responded.

“No, you don’t; that’s a truck up the street.”

A little later, someone remarked, “Maybe it’s just a test.”

“Test, hell!” was the answer, according to Miles. “You don’t throw that much metal into the air unless you’re fixing on knocking something down.”¹⁵

Elsewhere in town, reporter Ray Zemin asked a trio of police officers how many planes they saw.

“Oh, 150 or 200, I guess,” said one.

“They came in great dark clouds,” offered another.

The third officer disagreed: “Seven, maybe nine.”

Meanwhile, the searchlights coursed the sky, the bullets fired and the shells burst. Los Angeles, Zemin said, seemed to be “sitting on the lid of a bubbling volcano.”¹⁶

Confusion at the guns

The military was likewise confused. Once collected, reports suggested three camps: those who saw planes, those who saw a balloon or a dirigible, and those who saw nothing.¹⁷

At 3:28 AM, a gun commander reported 25 to 30 bombers over the Douglas airplane factory in Long Beach. Five minutes later, eight anti-aircraft batteries unleashed 581 rounds at supposed planes further inland. For half an hour, the sky over Long Beach was clear until a squadron of fifteen planes reportedly passed several times over the Douglas plant. At 4:55 AM, in came a report that the plant had been bombed. The report was false.

Another bad report claimed several enemy planes were downed between 190th and 180th on Vermont Ave. Word got out, and civilians flooded the area. There were no downed planes.

Three officers and a private from the 122nd gun battalion separately reported 15 to 20 planes flying a rigid V-formation. One Sergeant Bowman spotted the V as well in the spotlight, but said the formation reshaped into a T. These alleged planes did not appear on the radar.

Several officers from the 203rd anti-aircraft battalion and 214th field artillery regiment reported balloons, weather balloons and dirigibles, and despite training searchlights on the alleged objects, nothing appeared on the radar. In ten minutes, batteries fired 346 shells at a reported balloon over Santa Monica. Hundreds more shells went against a reported dirigible, but to no effect.

The reports of targets waned and firing quieted in the four o’clock hour. By 7:15, the sky was too light for the searchlights to be of use. At 7:20, the blackout order was lifted.

No planes, balloons or dirigibles were shot down. No U.S. planes were scrambled in pursuit of any target. The anti-aircraft battalions had shot roughly 1,430 explosive shells into the sky over the Los Angeles area.

The fallout

Shrapnel

Despite the fact that no bombs fell on Los Angeles, the region did sustain damage from the hail of shrapnel from the exploding shells of the U.S. Army.

Some shells did not explode in the air as intended, but fell as duds, such as the one that came through the roof of Victor Norman’s home in Long Beach. Other shells, like the one that hit the Landis family backyard, exploded on touching the ground. That shell ripped open the Landis’s garage, spraying their car with shrapnel. The flying metal also pierced the second floor and tore up a bed that had just been vacated.

On the following morning, according to the Bakersfield Californian, much of Los Angeles and its surrounding cities “took on the appearance of an egg hunt” as kids and grown ups competed to find the largest pieces of shrapnel.¹⁸

Deaths

The Battle of Los Angeles did exact a toll beyond property damage. At least six people died from incidental causes.

Sergeant Englebert Larson of the Los Angeles Police Department died in a vehicle collision while responding to an emergency call. Henry Ayers of the California State Guard, suffered a fatal heart attack while driving a munitions truck. George P. Well, an air warden, likewise died from a heart attack. Harry Klein died in a crash with a milk truck, and Jesus Alfarez and William Prince were both fatally struck by cars.

Distrust

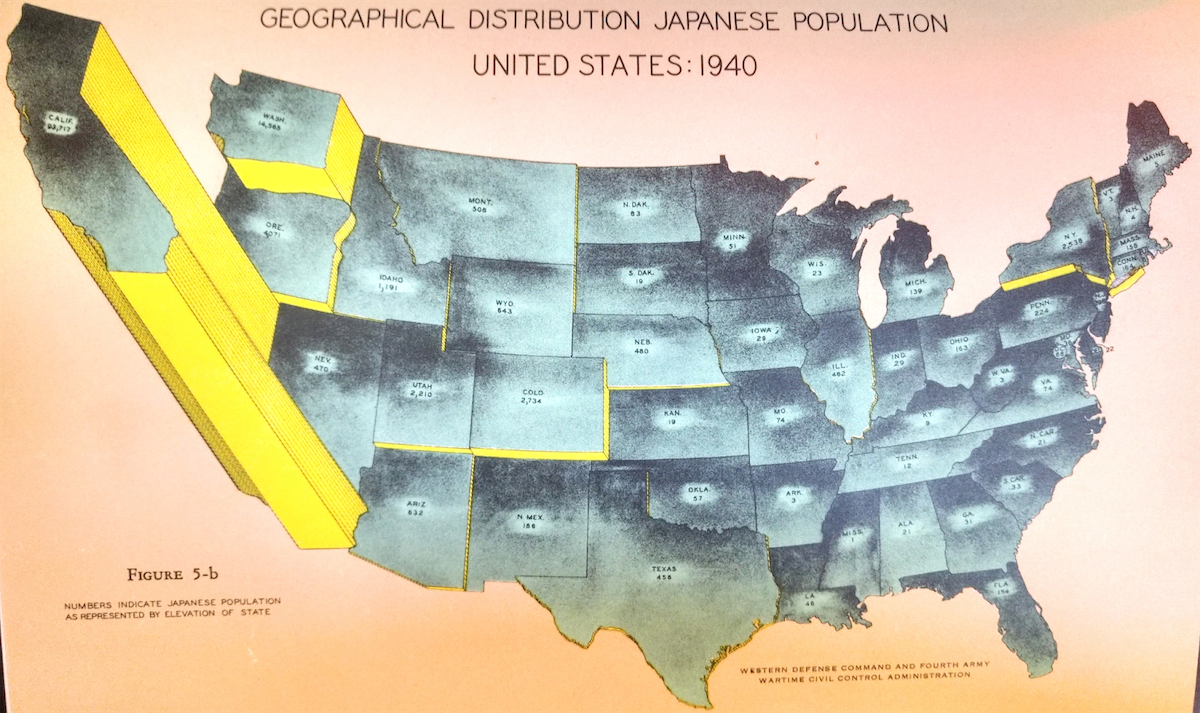

The most enduring, wide scale damage from the Battle of Los Angeles fell upon the Japanese-American community.

During the night of the battle, police arrested 30 people, 20 of whom were Japanese or Japanese-Americans. Police brought some in for banal violations of the blackout orders. One man, for instance, was arrested for driving after the siren in a truck carrying cauliflower.

Fifteen of the twenty, however, were arrested for alleged “fifth column” activities, meaning acts to aid the enemy.¹⁹ Specifically, several men were accused of signaling to the alleged planes.

A man named Yosuke Yamado in Compton was arrested for carrying flares. Police arrested Fred Konzo of Venice for flashing lights on his second floor. Four more men were brought in for the same. Police arrested Thomas Isomiosaki, 25 years old, for flashing his headlights.

Three days later, the U.S. House of Representatives Special Committee on Un-American Activities made public a report with findings that the Japanese were waging sabotage, espionage and propaganda campaigns within the U.S. under the guise of business and civic organizations. For instance, Japanese language schools in California, the report said, were “inculcating traitorous attitudes” in Japanese-American children and instilling an allegiance to Emperor Michinomiya Hirohito.²⁰

Within a few days, news coverage of the alleged danger posed by Japanese-Americans outweighed coverage of the Battle of Los Angeles itself. Racial animosity, it appears, fueled the fire of wartime fear. As reported by LIFE magazine: “Officials found themselves torn between a violent popular outcry for tough treatment of the Japs, and perverse apathy toward the even more numerous but equally dangerous Germans and Italians.”²¹

California legislators demanded that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt expand Executive Order 9066, the directive to relocate anyone of Japanese ancestry away from sensitive military sites.²² On February 28, California expelled Japanese-Americans from all civil service jobs.²³ In the following month, General DeWitt, under the authority of Order 9066, would remove everyone of Japanese heritage from the Los Angeles area and much of the West Coast. Within a year, the U.S. Government would summarily incarcerate over 100,000 people of Japanese heritage in internment camps.²⁴

Officials respond

Stimson v. Knox

On the day following the Battle of Los Angeles, U.S. Secretary of Navy Frank Knox held a press conference and declared that the incident was a “false alarm” due to “war nerves.” In Knox’s telling, no enemy aircraft had crossed the skies of Los Angeles.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson told a different story. According to Stimson, Fifteen enemy planes, likely “commercial services operated by enemy agents,” had taken to the skies. These pilots executed maneuvers over Los Angeles between three and four AM at heights of 9,000 to 18,000 feet to terrorize citizens of California.²⁵

In response to Knox, Stimson said, “My only comment is that perhaps it is better to be too alert than not enough.”²⁶

Three planes, two balloons

Once the U.S. Army’s Fourth Anti-Aircraft Command compiled reports, it honed the official explanation:

Two weather balloons were aloft over Los Angeles that night, accounting for sightings of balloons and dirigibles. As for planes, one to five but probably three enemy planes had flown over Los Angeles. They may have been civilian planes launched from within California, a neighboring state, or Mexico. Alternatively, Japanese submarines may have launched them. The I-17 submarine identified as the culprit behind the shelling of the Ellwood oil field had a watertight hangar and a catapult to launch a small airplane.

As for why the Army Air Force did not scramble planes in pursuit, General John Fickel and General DeWitt believed that the planes may have been executing a reconnaissance loop that would terminate at a Japanese aircraft carrier. If this were the case, and the U.S. had scrambled planes in pursuit, those U.S. planes would be low on gas by the time the larger Japanese force arrived.

In response to why the U.S. barrage of fire failed to knock anything from the sky, the report said the few targets — three planes, two balloons — were obscured by “over illumination” and a proliferation of false targets were created by the smoke and light. In the future, the Fourth Anti-Aircraft Command said, weather balloon launches ought to be prohibited while the coast is on active alert.²⁷

Mysterious origin

Dawn of the UFO

When the Battle of Los Angeles occurred, no account cited “flying saucers.” In fact, the incident predated the coining of the term “flying saucer” and even the “foo fighter” phenomena, in which WWII pilots reported UAP over Europe and the Pacific.²⁸

In 1947, however, while the U.S. was in the grips of its first major UAP sighting wave, the American writer Raymond Palmer made the connection between the Battle of Los Angeles and supposedly extraterrestrial flying saucers, albeit in the context of a science fiction story for the pulp magazine Amazing Stories. In 1952, another banner year for UAP sightings, Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Henry responded to a front page story on “432 Reports Written on ‘Aerial Phenomenon,’” by asserting that the Battle of Los Angeles had shown that mass hysteria can conjure nonexistent objects into the sky.³⁰

In 1967, Kenneth Larson, who had been an volunteer air warden during the incident, pioneered the argument in Flying Saucers Pictorial that the searchlights over Los Angeles that night had tracked a flying saucer. In 1968, Gordon Lore and Harold Denault of the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomenon further developed the argument in their book Mysteries of the Skies.

From there on, in books, articles and presentations, the Battle of Los Angeles became increasingly viewed as an early instance of UAP that for some provides evidence of non-human, intelligent beings.³¹

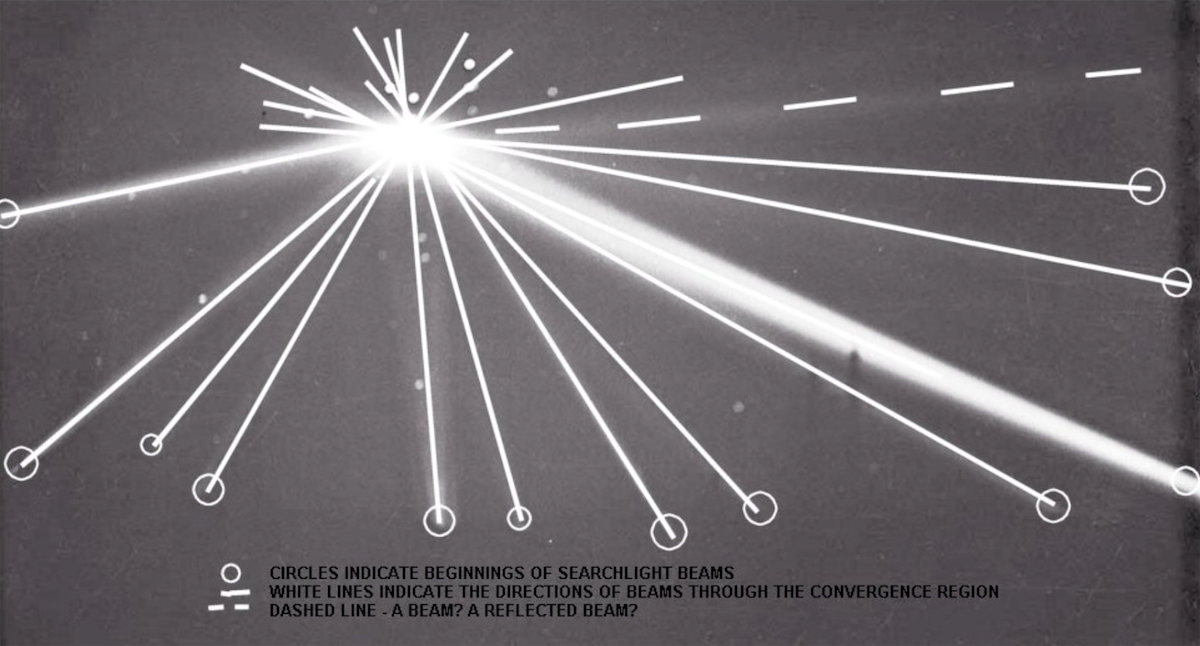

The Photograph

Core to many pro-UFO arguments for the Battle Los Angeles is the iconic photograph that ran in the Los Angeles Times on the day following the incident. The photograph appears to capture what thousands of witnesses reported: searchlights tracking an object as it slowly crossed over Los Angeles, apparently unfazed by exploding shells and high caliber bullets.

In examining the photograph, it’s important to note that the Los Angeles Times substantially retouched the image before going to print, a common practice at the time.³² Below is an unretouched version.

Dr. Bruce Maccabee, an UAP researcher and optical physicist with a long career with the U.S. Navy, found after examining multiple versions of the photograph and others photographs from the night that the brightened circle at the center of the beams appears to interrupt and reflect some of those beams, indicating an object. Additionally, the spread of the smoke in the images further support the likelihood of an object, Maccabee arged. Without detailed information on the camera, he said, his “wild rear-end guess” was that the object was 80 feet long.³³

Explanations for objects

Evidence beyond the photographs indicates that at least one object was in the sky that night. Army radar, though not consistent throughout the incident, tracked an object at 1:44 and 2:00 AM, and from 2:06 to 2:27 AM.³⁴ Moreover, while accounts diverged wildly and widespread hysteria certainly influenced perception, thousands of people reported spotting objects in the sky.

The Army’s hypothesis of three enemy planes, give or take, and two weather balloons satisfies the elements of many accounts. As mentioned earlier, witnesses described squadrons of planes at times in V formation. While those planes could not fly at 10 to 20 miles per hour, which was the apparent speed of the object tracked by the searchlights, that glacial pace would be appropriate to the alleged balloon or balloons in the sky.

Furthermore, some accounts described the object as a “barrage balloon,” a large, elliptical, tethered balloon that is visually similar to both a dirigible and the object in the photos of the converging searchlights. Barrage balloons were lofted up and down the coast as obstacles for aerial invaders, and one or more could have broken from their tether and drifted over the city.³⁵

(Other hypotheses have cited “fu go” balloons, the incendiary balloons released by Japan in WWII. The Battle of Los Angeles, however, predates these lighter-than-air weapons by approximately two years).

The Army’s explanation, however, strains on two fronts.

First, Japan has denied that it launched an attack on Los Angeles in the AM hours of February 25, 1942. This denial is particularly compelling considering that the Japanese government celebrated the shelling of the Ellwood oil fields and later admitted to attempting other raids on the U.S. West Coast, including a February 1942 mission on the southern Oregon coast.³⁶

Secondly, the explanation of three planes and two balloons, whether barrage or meteorological, struggles to satisfy the fact that the apparent targets of the Battles of Los Angeles went unharmed by thousands of high caliber bullets and over 1,400 explosive shells casting countless hot and jagged metal shards.

Presumably, the shrapnel would have torn open any lighter-than-air craft.

The Battle of Los Angeles, it seems, yet wants for explanation.