Summary

From November 1896 to May 1897, a curious phenomena swept the United States of America. People in California, the Midwest, Texas and elsewhere alleged sightings of lights and objects in the sky they most commonly described as “airships”. These witnesses, which may have numbered over 100,000,¹ often described craft of a size, speed and maneuverability that at once outstripped the available technology and jibed with popular fiction of the time.

A media craze sprung up around the sightings and produced over 1,200 newspaper articles, many of which fueled speculation on the existence of a mystery “aeronaut” behind the baffling reports.² Less often, “Martians” were credited.

Skeptics in turn offered rational attempts to explain the sightings, either as hoaxes or misidentification of natural phenomena. For many, these explanations fell short. The sightings died down after several months and their occurrence largely vanished from popular memory.

Still today, the strangeness of the claims, the sensationalism of the media coverage and the lack of systematic investigation trouble attempts to tease out the truth of the Airship Sighting Wave of 1896 to 1897. In this way and others, the accounts of the phantom airships closely resemble UAP sightings that would follow over the next century.

California

The first sightings

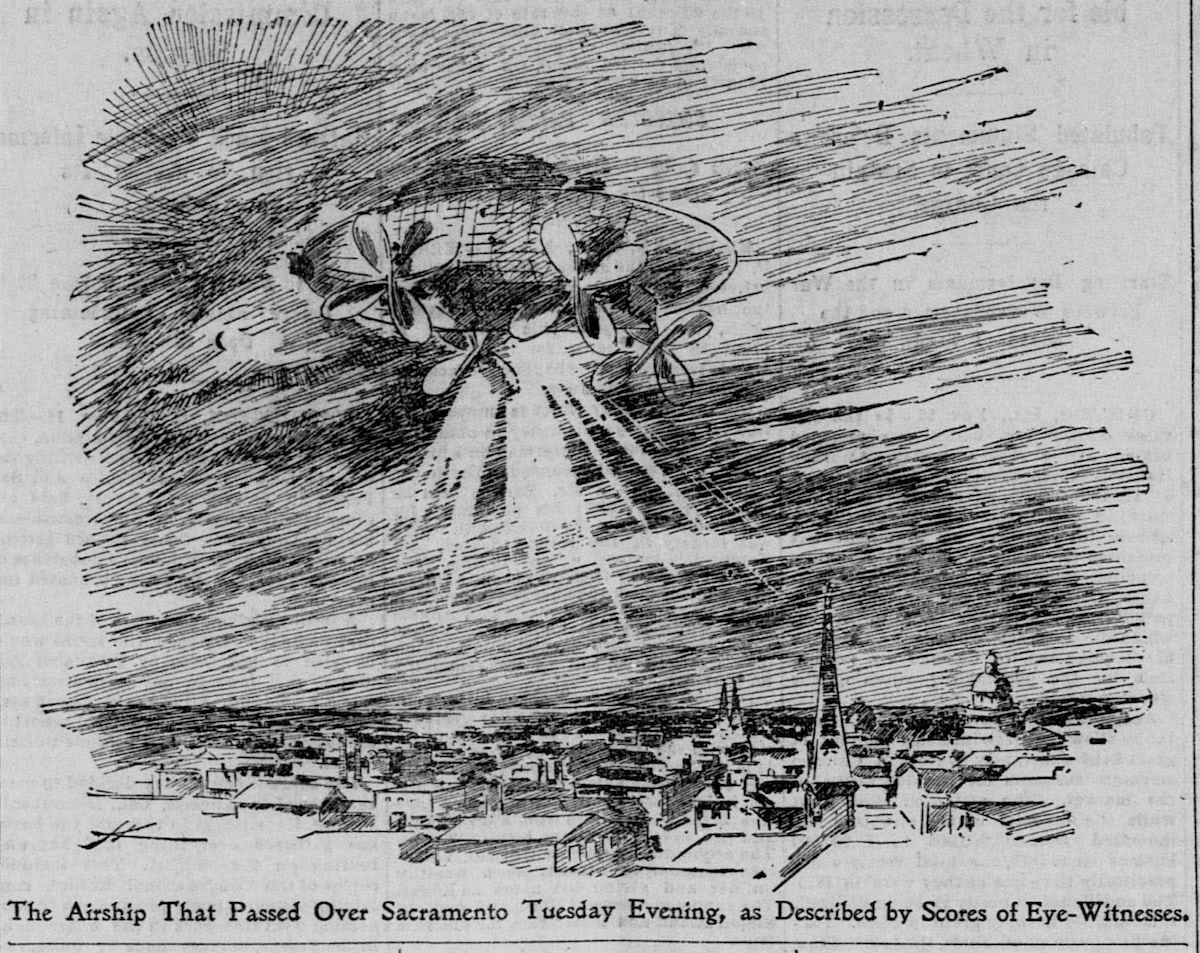

On November 17, 1896, a large object allegedly appeared in the night sky over the city of Sacramento, California, and shone a light down upon hundreds of onlookers. It resembled, according to the Sacramento Evening Bee, an “electric arc lamp” and it moved as though “propelled by a mysterious force.”³

A few nights later, a similar object allegedly hovered low in the sky over Oakland, California, and trained its lights on a streetcar. The object had the appearance of a hot air balloon turned on its side, reported the San Francisco Call.⁴

Another few nights on and the object seemed to reappear over Sacramento. This time it allegedly sped across the sky, but abruptly stopped for as long as twenty minutes, according to witness accounts from the Deputy the Secretary of State, Sacramento’s District Attorney and the Governor’s personal secretary, as reported by the Sacramento Evening Bee and the San Francisco Call. These witnesses insisted they knew how to pick Venus out of the night sky. This was not Venus, they said.⁵

So began the Airship Sighting Wave. Over the next few weeks, dozens more reports would appear in local newspapers. At minimum, witnesses described a powerful light. More often, they described an airship.

Airships and aeronauts

The state of flight

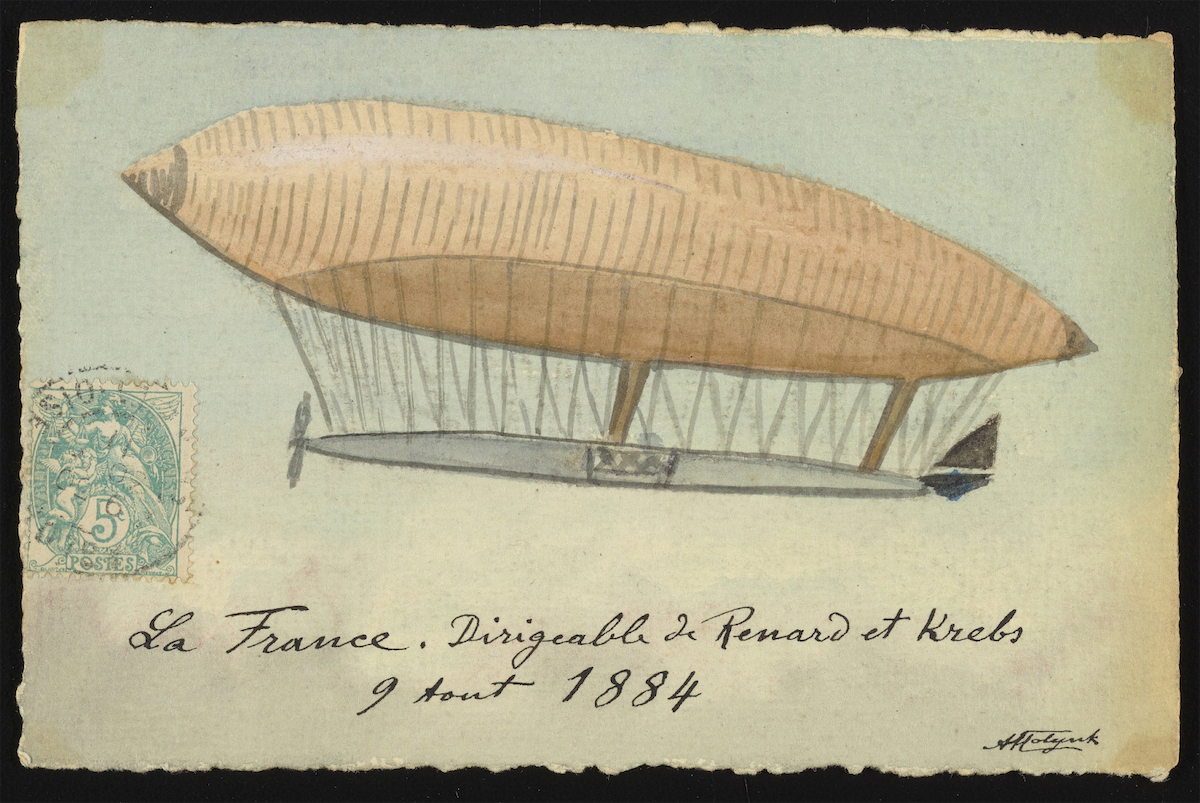

For the witnesses of the Airship Sighting Wave, an airship would mean a lighter-than-air, steerable flying machine that consisted of a long, occasionally rigid balloon and a ship, resembling a carriage or gondola, that hung from that balloon.

The sightings occurred mostly after dark, involving a broad variety of individuals and often crowds in the hundreds. The sightings would most often describe massive airships that hovered and crept slowly. At times, they allegedly skipped across the sky, made right angle turns and shot upwards, regardless of wind conditions.

Known airships of the time could not perform such feats of such speed and maneuverability.

Airships had existed in concept for a century, beginning with the sketches of aeronautical theorist Jean Baptiste Marie Meusnier who in 1784 proposed a balloon-tethered vessel powered by 80 men turning three propellers. Airships left the realm of theory in 1852 when Henri Giffard built and flew an airship out of Paris, France, at six miles per hour. In 1884, aeronauts Charles Renard and Arthur C. Krebs thrilled crowds by piloting their airship, La France, around the Eiffel Tower at a stunning 13 miles per hour.⁶

At the time of the Airship Sighting Wave, the most advanced airship in the U.S. was likely the pedal-powered “Sky-Cycle” piloted by “Professor” Arthur Barnard in Nashville, Tennessee.⁷ Like other state-of-the-art airships, the Sky-Cycle flew for crowds at fairs, covered short distances at a few miles per hour and rarely returned to its launch site. It could not steer against the wind.

Still, popular thought at the time held that if humans were to conquer flight, we would do so with airships. In 1896 and 1897, airship-related patents and their inventors, who sometimes claimed to work in secret, made news alongside the mysterious sightings.⁸ Moreover, newspapers shared the stands with yet more speculative aeronautical tales: the airships of late-Victorian popular fiction.

Airships of the mind

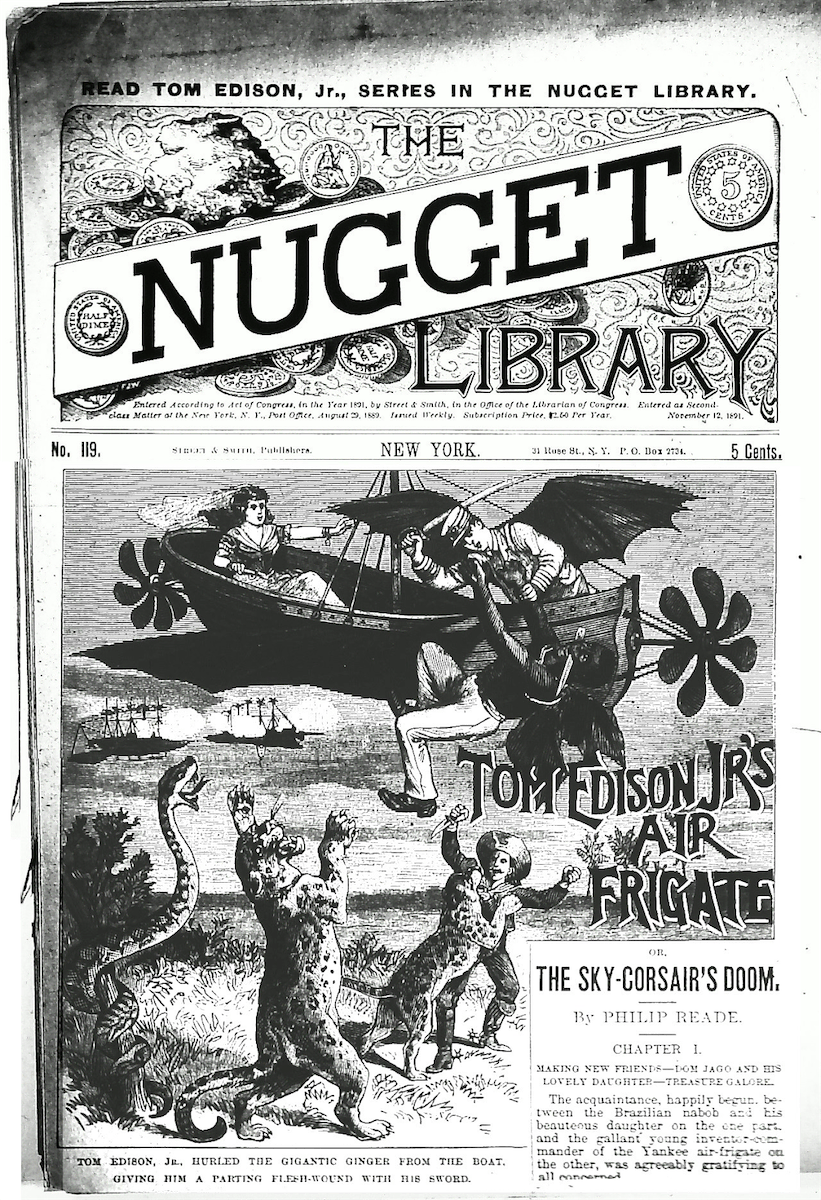

Airships loomed large in the popular culture of the 1890s.

In that decade, dime novels and serialized adventures featuring airships, such as The Balloon Detectives and Tom Edison’s Jr. Air Frigate, spiked in popularity.⁹ The plots would feature an intrepid aeronaut and the airship of his invention, such as witness Frank Reade, Jr. and his electric “sky yacht,” or the aforementioned Tom Edison Jr. and his “prairie skimmer.” The aeronaut was invariably on a journey across Mexico, Australia, the American west or some other landscape of high adventure.

The popularity of the airship dime novel did not materialize from the ether. It was a bankable genre created in the early 1870s by the most widely-read lighter-than-air fiction of all time: Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days.

Around the World was a smash hit, first as a novel selling 108,000 copies by the turn of the century and then as a touring stage play that reportedly earned Verne ten million francs.¹⁰ ¹¹

Verne’s fantastic tale inspired real adventure. Nellie Bly, a pioneering American journalist, famously followed the novel’s route and traveled the world seventy-two days, beating Fogg by a week and a day. The celebrated inventor and aeronaut Alberto Santos Dumont, whose gasoline powered airships were at the cutting edge of aeronautics, reportedly cited Verne’s fiction as his chief inspiration.¹²

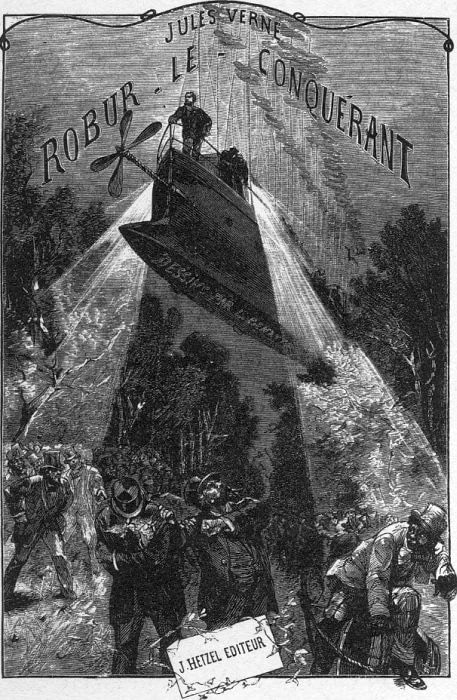

In the years approaching the Airship Sighting Wave, Verne himself revisited the motif with his airship novel Robur the Conqueror in which the titular rogue inventor flies his huge airship, the Albatross, on a menacing international spree.

Robur, like Around the World, was immensely popular and boosted the lore surrounding the image of the aeronaut.:

In the final scene before disappearing into the sky, Robur hovers over a crowd in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He proclaims that when they have sufficiently evolved, he shall return and share the secret of flight.

“And now, who is this Robur? Shall we ever know?” the novel’s narrator says in closing.

“Robur is the science of the future. Perhaps the science of to-morrow! Certainly the science that will come!”¹³

The aeronaut mystery begins

Considering the celebrated space the aeronaut held in late-Victorian popular culture, it’s no wonder that the sightings of alleged airships in California quickly inspired speculation over who had built these fantastic machines.

In November 1897, prominent Bay Area attorney George Collins stepped forward, claiming that he represented the inventor. Under pressure from reporters, Collins reportedly named one E.H. Benjamin, an itinerant dentist with a few patents to his name. As soon as his name appeared in papers, Benjamin vanished. Collins retracted his statements.¹⁴

William H. H. Hart, a former California Attorney General, also claimed to represent the inventor. The inventor, Hart told the San Francisco Call, flew from a secret location to which he returned each night to hide the airship in a barn. Hart, like Collins, soon retracted his story.¹⁵

Nevertheless, the notion that a great inventor was behind the sightings took hold.

The Midwest sightings

Omaha and elsewhere

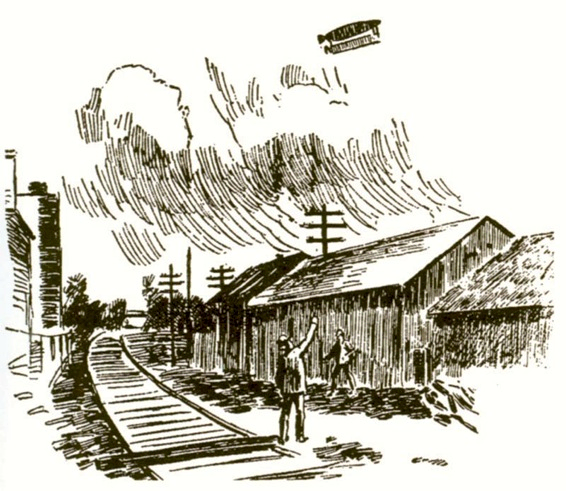

After dying down in California at the turn of the New Year, the sightings wave resumed in February 1897 over the skies of Nebraska. Newspapers such as the Omaha Daily Bee, The Sioux City Journal, The Valentine Democrat, The Red Cloud Chief, and the Nebraska Independent published dozens of accounts.¹⁶

As in California, some sightings alleged nothing more than a glaring light, whereas others alleged airships in detail. A church group outside of Omaha, for example, described a cone-shaped craft with a rudder and wings flying low enough that voices could be heard.¹⁷

Reactions ran the gamut from calls for “general measures” to teach citizens to distinguish Venus “blazing in the sky” to demands that the military stop the “mysterious and awful airship” from “careering in its mad course over Omaha.”¹⁹

The sightings spread beyond Nebraska. Hundreds of alleged sightings of an airship shining with red and green lights occurred in the following months in Midwest towns and cities. On March 28, the Topeka Daily Capital of Topeka, Kansas, reported mass sighting of an airship with a red light glaring down that city. On the following night, a similar object reportedly looped around the sky over Belleville, Kansas, and flooded the town with light for as long as half an hour.²⁰ In Everest, Kansas, two ships allegedly hung low in the sky and communicated via flashing lights.²¹

Hoaxes … with cows

Mixed throughout the sightings were hoaxes. In Omaha, pranksters reportedly sent up balloons with burning wood shavings. Practical jokers in Burlington, Iowa, replayed the trick. In Waterloo, Iowa, a few men staged an apparent crash site of a down airship. The community, taking the bait, organized search teams to find the supposedly missing aeronauts.²²

Perhaps the most enduring hoax of the Airship Sighting Wave involved a decidedly terrestrial creature: a cow belonging to a Kansas cattle rancher named Alexander Hamilton.

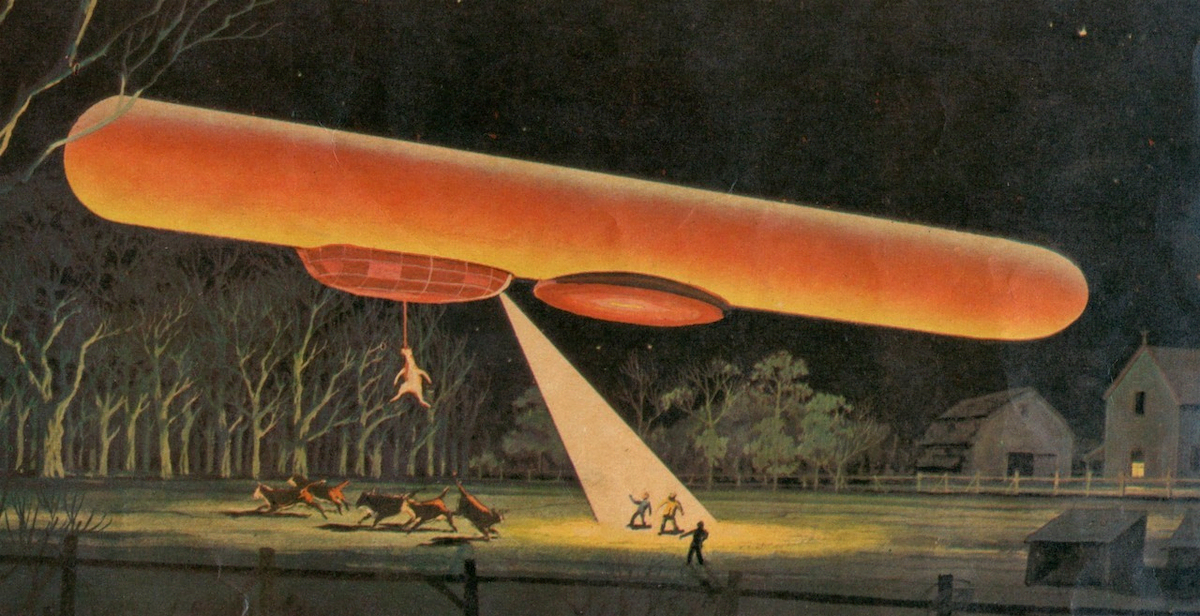

Hamilton and his friend E.F. Hudson, editor of a local paper called theYates Center Farmers’ Advocate, reportedly concocted a tale wherein a 300-foot long, cigar-shaped airship lassoed one of Hamilton two-year old heifers and carried the cow off into the night.

Hamilton said the airship’s carriage was transparent, brightly lit and “occupied by six of the strangest beings I ever saw.”

Hamilton also said that on the following day, the animal was found in pieces across a series of fields. “After identifying the hide by my brand, I went home,” he said.²³

The story ran in great detail in the Farmers’ Advocate on April 23, 1897, and came with an affidavit signed by twelve men, including a local sheriff, a judge and the postmaster, to attest to Hamilton’s credibility.

The affidavit itself, however, was part of the prank. Hamilton and Hudson (and likely some of the affidavit signers) were part of a local “Liars’ Club” where men would one-up each other by passing-off tall tales. Hamilton’s cow-knapping story was one particularly audacious instance of the tradition of entertaining lies.²⁴

Media hype

Other newspapers got in on the act. The Peoria Transcript in April 1897, reportedly launched lighted balloons to expose the Airship Sighting Wave as a mix of hoax and hysteria.²⁵ In a similar move, the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune ran a phony picture of an airship, intending to demonstrate how easy such a fraud would be.²⁶

If nothing else, the Airship Sighting Wave was a media phenomenon, and reactions in the press were as varied as the newspapers themselves. Some reported sightings with breathless credulity, others with derision. Some papers apparently fanned the flames, reporting, for instance, that the mystery aeronaut could be a Cuban terrorist.²⁷ ²⁸ ²⁹ Others adopted a skeptical tone. The Des Moines Leader and the Baltimore News, for example, asserted that the wave was an episode of mass delusion.³⁰

(Readers should note that while newspaper coverage was constant, attention to that coverage waned; In California, at the start of the wave, the sightings ran on the front page with elaborate illustrations. By the time the sighting wave reached Texas, newspapers gave sparser detail and buried the stories deep within their pages).

Hysteria undoubtedly played a role in the sighting wave. The Detroit Free Press, for instance, reported that crowds gathered in Iowa towns where sightings were anticipated. In Milwaukee, hundreds reportedly gathered on the rumor that an airship would appear. When a passing streetcar set off sparks from a lofted wire, the crowd allegedly cried out with wonder.³¹

Venus

In addition to hysteria and hoax, astronomers offered explanations:

Professor G.W. Hough of the Dearborn Observatory said that an airship sighting over the northern edge of Chicago, which thousands of witnesses allegedly traced from block to block, was actually a single star in the constellation Orion.³²

Father Rigge, an astronomy professor at Creighton College in Omaha, explained the sightings over his city as the appearance of Venus.³³ Other astronomers cited Betelguese or Jupiter as the culprit.

In response to astronomical explanations, the Chicago Tribune countered that “Venus does not dodge around, fly swiftly across the horizon, swoop rapidly toward, then soar away until lost in the southern sky.”

The Tribune floated an alternate, somewhat mind-bending theory: “the vessel,” the paper said, “is purely a celestial body which has taken on a few attributes in order to accommodate itself to the limitations of human imagination.”³⁴

Southern sightings

A man called Wilson

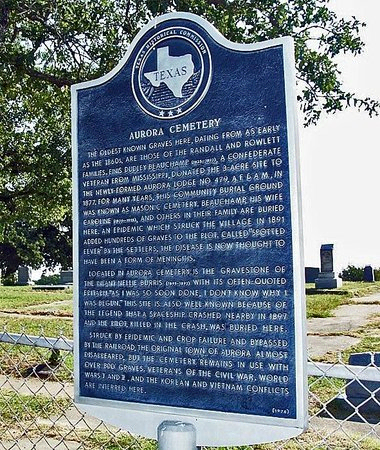

From the Midwest, the sightings wave went south. Upon reaching Texas and Louisiana, the accounts grew substantially more specific with regard to the mystery aeronaut. In particular, in the third week of April 1897, witnesses in Beaumont, Greenville, Austin, Ladonia, Waxahachie, Wortham, Uvalde, Josserand, and Koutze, Texas, and Lakes Charles, Louisiana, alleged contact with an airship and its aeronaut. The aeronaut allegedly introduced himself as “Wilson.”³⁵

For several weeks following, accounts appeared on a near-daily basis in Texas newspapers. Commonalities about “Wilson” and his ship emerged: his airship was one of a fleet of five; he kept the fleet in Iowa; the airships ran on an electric motor; and he was originally from a town in Upstate New York.

“I was so dumbfounded,” a witness identified as Rabbi Aaron Levy told the Houston Daily Post after allegedly coming across Wilson and his airship on a country road, “I couldn’t frame an intelligent question to ask.”³⁶

The Houston Post reported that an aeronaut instead insisted to a witness, “call me Smith.” The aeronaut Smith allegedly gave the witness a $10 bill to buy “lubricating oil,” telling him to keep the change. Smith used the oil for a repair and then took off in his airship “like a shot out of gun,” the witness said.³⁷

Another sighting out of Cisco, Texas, had the aeronaut explain that he was transporting dynamite to Cuba. One ex-Arkansas senator identified as Harris, said that the aeronaut offered him a ride to Cuba to go “kill Spaniards.”³⁸

Professor Rigge of Creighton College weighed in again, saying that a “fellow in the backwoods” could not build an airship of the sort alleged when so many others had failed.³⁹

A document appeared in the press alleging that the mystery aeronaut was famed inventor Thomas Alva Edison. Edison called the document a “pure fake.”

Edison added that he had “no doubt that air-ships will be successfully constructed in the near future,” however, he found it “absolutely absurd to imagine that a man would construct a successful air-ship and keep the matter secret.”⁴⁰

Stranger encounters

Martians and other beings

As odd as the aeronaut accounts were, the sightings wave included yet more puzzling accounts. In the interest of not presenting too-simple a picture, here are a few examples:

As with airships, albeit to a lesser extent, extraterrestrials were a popular subject in fiction and the news media, and of course, the notions drawn from this popular discourse may have influenced the perceptions of witnesses.

In 1897, for example, the epoch-making writer H.G. Wells published The Crystal Egg, a story in which the titular object provides a looking glass onto Martian civilization. More importantly, that year witnessed the serial release of The War of the Worlds, one of Wells’ most successful novels.

Meanwhile, the press often speculated on the actual possibility of Martian life. For example, just before the Airship Sighting Wave began, the Indianapolis Journal and the New York Herald ran articles on the make up of forests on the red planet.⁴⁴ Such theorizing largely began with the supposed discovery of “canals” on the red planet in 1877.⁴⁵

Looking back

The Airship Sighting Wave dropped off in the early summer of 1897 and despite its massive reach, the baffling saga was largely forgotten. A dozen years later when a similar wave occurred in New England no apparent connection was made to its nationwide predecessor.⁴⁶

For some, the Airship Sighting Wave is primarily instructive as a case of mass hysteria.

According to Dr. Ronald E. Bartholomew, a sociologist who specializes in mass hysteria, the U.S. in the late 1890s was in a state of anxiety that left it vulnerable to such an episode:

The technology of telephones and electricity was reconfiguring the world at a rapid clip. The trauma of the Civil War lingered, and violent conflict with Spain, an imperial power, appeared inevitable. Meanwhile, the media and popular culture proclaimed that a great inventor would soon conquer the air and would do so with airships.

Under these conditions, according to Bartholomew, the U.S. public drew the elements of anxiety into a narrative that “redefined the situation” and reassured them of “man’s dominance.”⁴⁷

Dr. Jacques Vallee, an astronomer turned data scientist and UAP researcher, sees another possibility, one that also incorporates the historical anxieties and the power of perception.

Vallee argues that airships may have been the work of a non-human intelligence. This intelligence might shape its physical manifestations according to the developments of our culture. The behavior and appearance of the phenomena, Vallee proposes, exists in transaction with our expectations.

This intelligence may be at the root of not only the phantom airships of the 1890’s, but also our supernatural myths and sightings of UAP more broadly. Vallee further theorizes that the strangeness of the encounters serve to keep them outside of our sensible explanation of how the world works.

“Perhaps the airship,” Vallee says, “like the fairy tricks, the flying saucers, was a lie so well engineered that its images in human consciousness could sink very deep indeed and then be forgotten — as UFO landings are forgotten, as the appearance of supernatural beings are forgotten.”⁴⁸