Summary

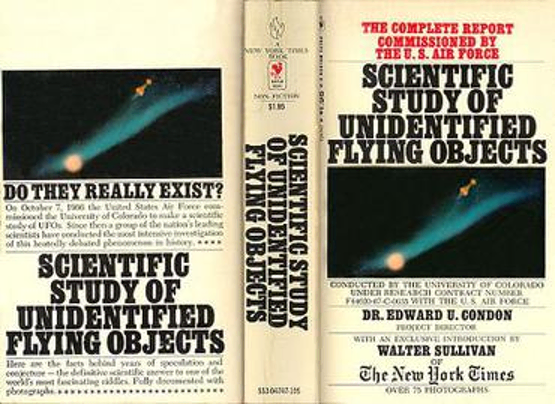

The Condon Committee was a large-scale investigation into UAP reports carried out at the University of Colorado from October 1966 to November 1968 under the direction of physicist Dr. Edward Condon. The U.S. Air Force contributed the bulk of the reports and funded the project. The committee produced a 1,439-page final report titled Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects¹ for which Condon wrote a summary section and a conclusions and recommendations section. Condon’s sections, which recommended against further study into the UAP phenomenon, became the subject of controversy as readers of the report, including researchers on the committee itself and multiple scientists contributing to the project, found it at odds with the content of the report’s findings.

Leading up to the "Colorado Project"

The Condon Committee came about as a result of popular interest in UAP sightings, a succession of U.S. Air Force projects into the phenomena, and the efforts of interested scientists and high profile political figures, including then U.S. House of Representatives Minority Leader and representative of Michigan’s 5th congressional district Gerald Ford.

Following a rash of highly publicized UAP sightings in 1965 and early-1966, some of which came from in and around Ford’s district, Ford proposed a congressional inquiry into the UAP phenomena, saying, “I think the American people would feel better if there was a full-blown investigation of these incidents.”²

In response, the Committee of Armed Forces of the House of Representatives held hearings on April 5, 1966, during which it received testimony from U.S. Air Force Secretary Harold Brown and Dr. J. Allen Hynek, an astrophysicist and long-time consultant to the U.S. Air Force’s UAP investigation body, Project Blue Book. The Committee of Armed Forces concluded that the Air Force’s efforts through Project Blue Book and its previous iterations, Project Sign and Project Grudge, had fallen short. As the Committee noted, the projects had collected over 10,000 reports in almost two decades and yet Project Blue Book was presently staffed with only one officer, one sergeant and one secretary. The Committee suggested the Air Force partner with universities and a non-profit organization to perform a more thorough investigation into collected and incoming reports.⁴

A month prior to the hearings, the U.S. Air Force Scientific Advisory Board, which included astronomer Dr. Carl Sagan, had arrived at a similar conclusion. In part at the urging of Hynek, the board resolved to undertake a comprehensive review of Project Blue Book’s files.⁵

The Air Force’s search for a partnering organization for the undertaking landed at the University of Colorado, where physics professor Dr. Edward Condon, a pioneer in quantum physics,⁶ offered to direct the project. The project referred to itself as the “Colorado Project” in documents, though it is more commonly known as the “Condon Committee.” Answering to Condon was Robert Low, an assistant dean at the University of Colorado. Beneath Low were principal investigators Dr. David Saunders, a psychologist, and Dr. Franklin Roach, an astrophysicist. According to the Committee’s final report, the project employed a staff of 37 and received $313,000 in initial funding from the U.S. Air Force. In addition to Project Blue Book files, the Colorado Project received UAP reports from the Aerial Phenomena Research Organization, or APRO, and the National Investigations Committee for Aerial Phenomena, or NICAP.⁷

The Colorado Project began its work in October 1966 and concluded its research in a little more than two years.

The Report

Selecting incidents for investigation

In sifting through thousands of UAP reports, the Condon Committee selected 59 incidents as “case studies.” According to the Committee, these 59 incidents tended to present evidence that was, to varying degrees, illuminating, dispositive or in some sense fruitful in determining whether the larger UAP phenomenon merited systematic, large-scale scientific investigation. The Committee laid out its criteria for such evidence in Section III of the final report.⁸

According to its own account, the Committee hewed towards incidents with multiple eyewitnesses who possessed determinable credibility, whether reliable or not, and with whom the Committee could follow up.⁹ In regard to photographic evidence, the Committee considered only images that had multiple witnesses and elements that would help indicate height, distance, motion, qualities of light, and potential manipulation. The Committee selected in favor of files that recorded direct physical evidence, such as burn marks on the ground, or analysis of materials allegedly left behind by a UAP, and indirect physical evidence, such as car malfunctions, physiological reactions, lapses in consciousness, television and radio interference, etc., allegedly linked to a UAP sighting. The Committee also favored incidents that came with radar evidence to corroborate sightings. Finally, the Committee put high premium on UAP sightings from astronauts, considering these witnesses’ categorically superb eyesight and high degree of knowledge in atmospherics and astronomy, as well as the extensive records and debriefings attending their missions.

A few of the 59

For the majority of the 59 cases, the Committee arrived at explanations where witnesses misidentified natural or manmade phenomena, for example, mistaking lenticular clouds or satellites for flying saucers. A few cases were the result of deliberate falsification, according to the Committee. Oftentimes, the Committee bundled its conclusion into the title of case study, such as “Bright Planets Perceived as UFOs” and “Prank with Plastic Dry-Cleaning Bag.”

Other cases presented more perplexing findings, and the given researchers at times conceded that the incident remains unexplained.

For example, in 1965, Gemini VII astronaut Frank Borman, who had logged 330 hours in space, told ground control that a “bogey” was flying “at 10 o’Clock high” in formation with his spacecraft. Borman distinguished it from “space debris,” and his crew mate James Lovell, who would achieve 425 hours in space, corroborated the sighting. Condon Committee principal investigator and astrophysicist Franklin Roach listed this sighting along with two from Gemini IV astronaut James McDivitt as the only incidents to remain inadequately explained among the dozens of reports from astronauts on curious phenomena.¹⁰

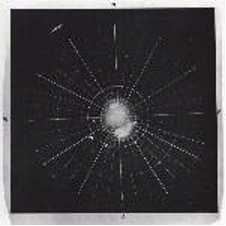

Another unexplained case took place near Greenwich, U.K., where in 1956 a control tower on a joint U.S. Air Force and U.K. Royal Air Force base picked up a hovering object on its radar. The base scrambled two RAF planes to intercept. The first plane to near the object locked guns on it, at which point, according to the pilot of the second plane and continuous radar records from the tower, the object swooped around to the tail of the first plane. The object now appeared to be two objects that moved as though “glued” to the first plane, pursuing it closely despite evasive maneuvers until, after ten minutes, the object, once again singular, resumed hovering. The object was now out of radar range. The pilot of the first plane reported engine malfunction. The planes returned to base.

The Condon Committee staff investigator concluded, “the probability that at least one genuine UFO was involved appears to be fairly high.”¹¹

In other cases, the Committee investigators offered explanations that mix explained phenomena with unexplained phenomena.

For instance, case number 6 details a sighting from 1966 that began with a young girl in the northeastern United States spotting a bright light from her window at 9pm in the evening. The girl informed her father, who was simultaneously contending with apparent electrical malfunction in the television. Shortly afterward, two neighbors spotted the light over a nearby high school. The light reportedly became three lights that darted back and forth over a field. More eyewitnesses gathered, some of whom later described the lights as objects with flat, metallic bottoms. One of the objects reportedly lowered to within 20 feet of the ground, causing onlookers to fear being crushed. The object allegedly rose up and tilted on edge. Police arrived and took part in the sighting, which by now had gone on for thirty minutes. The three objects left the area over the high school, and the police pursued until the objects again appeared as one, at which point it disappeared.

The Committee investigators attributed some of the sighting to the planet Jupiter.¹²

Finally, another category of sightings emerged in the case studies, one where the evidence offered is so confusing that little explanation was attempted.

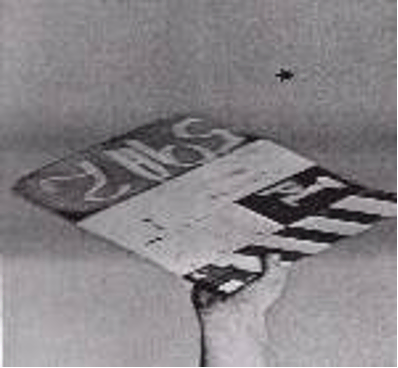

For instance, a study titled “Claim of UFO Landing” told of a mechanic who was “weekend prospecting” in the Canadian bush when he allegedly witnessed a UAP touch down. The mechanic, called “Mr. A” in the study, reported that he found the UAP, which he described as a large, metallic cylinder that had an open hatch door. A bright light from the hatch door reportedly obscured any view within the vessel. Mr A called into the hatch door in multiple languages, including Russian and Ukrainian, and after failing to receive an answer, Mr. A touched the surface of the object.

According to Mr A, some manner of exhaust instantly burned him. He took off his shirt, which was in flames, and stamped it on the ground, he reported. Mr. A sought medical attention. Patterned burns had appeared across his stomach and the remaining shreds of his shirt. He reportedly lost 22 pounds in the following week.

The incident occurred while the Condon Committee was at its work, and a Committee investigator met with Mr. A in Canada to find the site in the woods.

“This ‘search’ impressed the investigator, as well as other members of the party, as being aimless,” the Committee’s report says. The search was abandoned; although sometime later, Mr. A allegedly recovered scraps of metal left by the craft.

“If Mr. A's reported experience were physically real, it would show the existence of alien flying vehicles in our environment,” the Committee said. However, the Committee said, “this case does not offer probative information regarding inconventional craft.”¹³

Problems of evidence

Following its discussion of the selected cases, the Committee ran once again through the categories of evidence it considered, but this time in order to elaborate on the challenges each one presents in determining the truth.

Problems of perception are rife throughout UAP reports, the Committee said, noting that each is a chain of perception, conception, and reporting, vulnerable to distortion at each step. Considering the lack of physical evidence and the pervasiveness of perceptual problems, “the number of truly extraordinary events, i.e. sightings of alien spaceships or totally unknown physical-meteorological phenomena, can be limited to the range 0-2% of all the available reports, with 0 not being excluded as a defensible result,” wrote astronomer and Committee author Dr. William K. Hartmann.¹⁴

Subsequent chapters reviewed the challenges posed by yet misunderstood atmospheric electricity, the compelling but misleading nature of optical mirages, and the expertise and corroboration required to interpret radar. Why is it, wonders Dr. William Blumen, Committee author and astrophysicist, that reported UAPs failed to produce any sonic boom when apparently traveling beyond the speed of sound?

With the exception of Hartmann, the authors reviewing these evidentiary problems did not carry out any of the project’s case studies.

Condon’s Conclusions

Of the over 1,400 pages of the Condon Committee report, Edward Condon himself wrote the first 77-pages: the “Conclusion and Recommendations” and “Summary of the Study” sections placed at the front of the document.

In his summary, Condon went over a brief history of the UAP phenomena, the origin of the project, a definition of terms, the research plan, and his skepticism of the “extraterrestrial hypothesis” that alien beings were manipulating the UAPs. After reviewing the immense distances of cosmic space, Condon said, “In view of the foregoing, we consider that it is safe to assume that no ILE,” meaning intelligent life elsewhere, “has any possibility of visiting Earth in the next 10,000 years.”¹⁵

Condon’s “Conclusions and Recommendations” were similarly negative on the prospects of further study into the UAP phenomena. The project did not reveal any “fruitful lines of advance from the study of UFO reports,” Condon said, adding that the field as a general matter of scientific inquiry should not be supported.

In closing, Condon urged “that teachers refrain from giving students credit for school work based on their reading of the presently available UFO books and magazine articles.”

Teachers ought to direct UAP inclined students towards “serious study of astronomy and meteorology, and in the direction of critical analysis of arguments for fantastic propositions that are being supported by appeals to fallacious reasoning or false data.”¹⁶

Controversy

The critics

Controversy surrounded the release of the Condon Committee’s report with critics asserting that Condon’s remarks ran against the findings within the case studies.

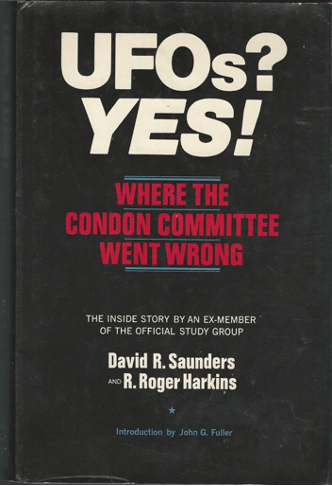

Among the vocal critics was Dr. David R. Saunders, a psychologist and principal investigator on the project. Saunders laid out his critique inUFOs? Yes! Where the Condon Committee Went Wrong, a book written with journalist Roger Harkins and released before the Committee’s final report was published. According to Saunders, Condon had bias against the “extraterrestrial hypothesis,” exaggerated “crackpot” elements of UAP sightings, alienating APRO and NICAP contributors, and underplayed the findings of field investigators in favor of specialists who were less involved in the particulars of a given case.¹⁷

Quoted in a January 1969 New York Times article, Saunders said that the report would “lack the essential ingredient of credibility.”¹⁸

Another major critic was Dr. James McDonald, a physicist and meteorologist at the University of Arizona and longtime advocate for investigation into the extraterrestrial hypothesis. McDonald critiqued the Committee’s final report in an address he delivered to the American Association for the Advancement of Science called Science in Default: Twenty-two Years of Inadequate UFO investigations. McDonald asserted that the Committee took on a “tiny fraction of the most puzzling cases” and of those examined, up to a third could be characterized as unexplained. After going through select cases with exhaustive detail, McDonald asserted that Condon’s summary and conclusions were a “stunning nonsequetir” with regard to the content of the reports.

Dr. J. Allen Hynek, who had been instrumental in the lead up to the Committee, also found contradiction between Condon’s remarks and the body of the report. “The Condon report settled nothing,” Hynek said in his 1972 book The UFO Experience: A Scientific Inquiry. “However, carefully read,” Hynek continued, “the report constitutes about as good an argument for the study of the UFO phenomenon as could have been made in a short time.”¹⁹

Troubled beginnings

In August 1966, months before work began, Robert Low, Assistant Dean at Colorado University and the Committee’s project coordinator, wrote a memo assuring university administration against the possibility of identifying “flying saucers.”

According to an article in the May 14, 1968, issue of Look magazine, Low told administrators that the “trick would be, I think, to describe the project so that, to the public, it would appear a totally objective study but, to the scientific community would present the image of a group of nonbelievers trying their best to be objective but having an almost zero expectation of finding a saucer.”²⁰

According to the Look article, which quotes multiple Committee staff members, the memo bothered researchers on the project as a sign of undue bias. Principle Investigator Dr. David Saunders passed the memo to Dr. James McDonald, who made it public and subsequently suffered an alleged attempt from Low and Condon to have him fired from the University of Arizona. Saunders, Dr. Norman Levine, an engineer and Committee researcher, and an administrative assistant allegedly lost their jobs on the Committee in the fallout of what became known as the “Low Memo” or “Trick Memo.”

Meanwhile, in the first year of the project’s work, Condon himself was quoted in the Denver Post, Rocky Mountain News and the Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York, as disparaging in separate, public incidents the possibility that scientific value could emerge from the Committee, according to Look, which cites the newspaper articles.

As a result of the “Low Memo” and a loss of confidence in Condon’s impartiality, NICAP director Major Donald Keyhoe, U.S. Marine Corp retired, announced in May 1968 that the organization would break ties with the Colorado Project.

In particular, Keyhoe objected to the fact that Condon himself did not investigate the cases considered by the Committee.²¹

Conclusion

Critics such as Saunders, McDonald and Hynek worried that Condon’s remarks at the front of the report would convince influential readers, such as members of the House of Representative to whom it was submitted and high ranking U.S. Air Force officials, that the UAP phenomenon did not merit serious attention. Sure enough, the USAF terminated Project Blue Book in December 1969.

However, as Hynek and others pointed out, the body of the report extensively detailed multiple cases of sighted aerial phenomena that remained unexplained despite examination from astrophysicists, meteorologists, psychologists and experts from the fields of radar and photography. The Condon Committee, whatever the conclusions drawn from the document, nevertheless memorialized illuminating evidence in the consideration of the UAP phenomenon.