Summary

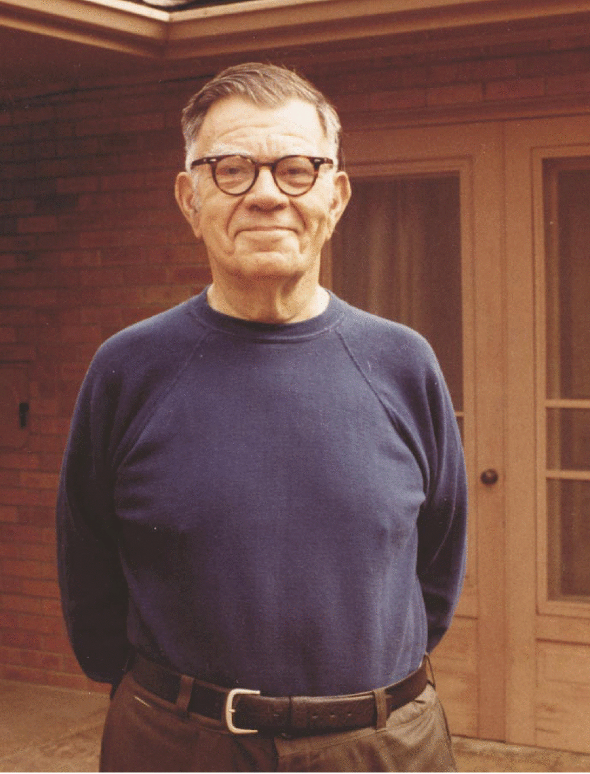

Dr. Edward Condon was a pioneering American physicist and the scientific director of the Colorado Project, frequently referred to as the Condon Committee, a two-year, investigation at the University of Colorado into UAP reports amassed primarily by the United States Air Force. The project, which was funded by the U.S.A.F., became largely known for Condon’s conclusion that scientific study into the UAP phenomenon was “fruitless.”¹

Despite the influence of Condon’s remarks — prompting the U.S.A.F. to close its UAP investigative body, Project Blue Book — several prominent researchers argued that Condon’s remarks betrayed his own bias and ignored significant findings within the Colorado Project report.²

To appreciate Condon’s influential yet divisive role in the history of the UAP phenomena, a glance at his life prior to the Colorado Project illustrates how Condon was at once a seminal figure in 20th Century science and, at turns, an outsider embroiled in controversy.

Establishing Bona Fides

Edward Uhler Condon was born in 1902 to a working class Quaker family in Alamogordo, New Mexico. At the age of 16, Condon landed a job as a reporter in California’s Bay Area. The young Condon covered crime and labor on the Oakland docks for three years until, disillusioned, he entered the University of California, Berkeley.³ Condon turned to science and at the age of 26 earned a PhD with a groundbreaking dissertation on the effect of light on molecular behavior, establishing what became known as the Franck-Condon principle. In the following year, Condon studied quantum physics in Germany and co-authored both the first English-language book on the subject and the first scientific paper demonstrating quantum mechanics within atomic nuclei.⁴ ⁵

In and out of favor

During World War II, Condon helped develop airborne radar for the National Defense Resource Council at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then took a short-lived job as associate director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, commonly known as the Manhattan Project, the effort that produced the world’s first atomic bomb. Condon, put off by the secrecy and paranoia surrounding the project and, more specifically, the command of U.S. Army Corps of Engineer Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, left after six weeks.⁶

As Condon would later testify to the U.S House of Representative Committee on Un-American Activities, or HUAC, “I didn’t want my family locked up inside a fence and I didn’t want to wear a uniform.”⁷

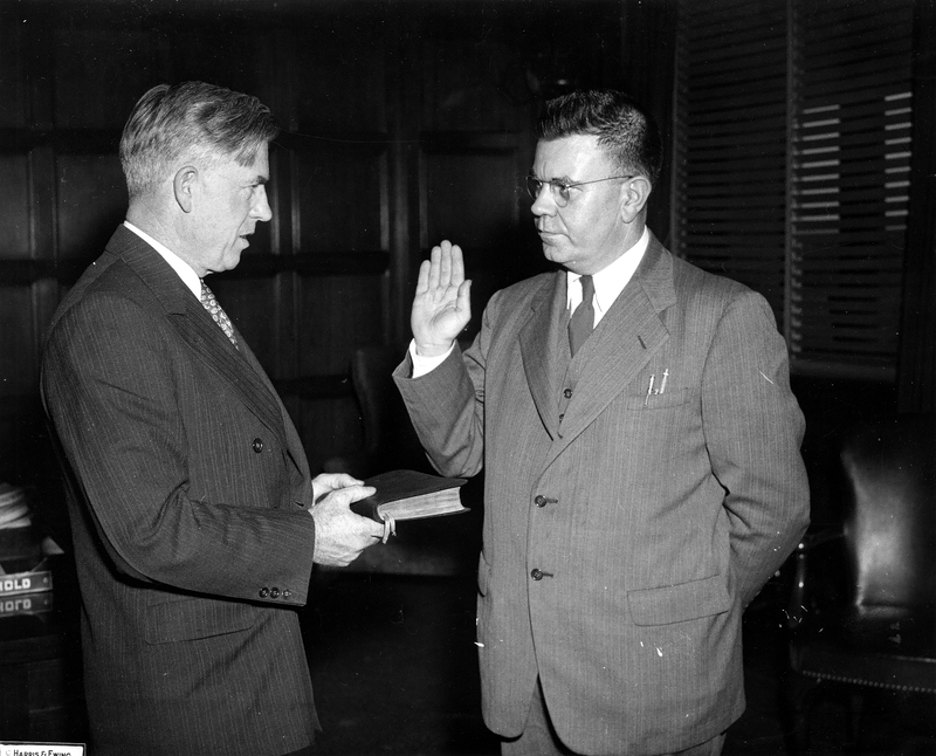

Following WWII, Condon became a vocal advocate for civilian control of nuclear technology and won appointment from U.S. President Harry S. Truman to chair the National Bureau of Standards, later called the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

The appointment caught the attention of HUAC, which would call Condon to appear multiple times between 1947 and 1952. HUAC’s questions to Condon included, for example, how he justified speaking with scientists who were alleged communists; how he happened to be born near the later-birthplace of the atomic bomb; the nature of his wife’s politics; and whether the “revolutionary” field of quantum physics predisposed him to other “revolutionary” notions.

Condon’s replies were often sardonic.⁸

Federal Bureau of Investigations Director J. Edgar Hoover characterized Condon as “nothing more or less than an espionage agent in disguise,” according to Department of Labor Secretary Daniel Moynahan.⁹ Albert Einstein, the entire physics department of Harvard University and nine Nobel prize winners wrote in Condon’s defense, but ultimately, Condon lost his security clearance, allegedly at the urging of then Vice President Richard Nixon.¹⁰

Condon resigned from government work, shifted his career towards teaching and in 1963, joined the staff at University of Colorado.

The Colorado Project

In the summer of 1966, Condon accepted an offer to direct a civilian-led, Air Force-funded investigation to determine whether UAP reports warranted ongoing scientific inquiry. In a little over two years, Condon would conclude that the phenomena was “fruitless” as a field of scientific study.¹¹

According to the Condon Committee’s final report and others who criticized his conclusion, Condon himself did not investigate any reports. In those two years, however, Condon participated in UAP issues, albeit in a manner later critics would say catalyzed a prejudice against serious study into the phenomenon, a bias that physicist Dr. James McDonald characterized as a focus on the “crackpot fringe.”¹²

In January 1967, while addressing Sigma Xi, a honorary scientific fraternity, Condon said that he’d “recommend that the Government get out of this business,” and that “there’s nothing to it,” according to a May 1968 article in Look magazine, drawing the quote from the Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York. Condon reportedly added with a smile, “I’m not supposed to reach a conclusion for another year.”¹³

A few months later, according to Condon, he was visited by a man claiming to be an agent of the “Third Universe”. The self-purported agent allegedly told Condon that the “Second Universe” was inhabited by beings resembling polar bears, whereas the beings of the Third Universe had perfected space travel technology, a technology this agent said that he could teach Condon for a fee of $3 billion. The agent allegedly said that he’d be willing to start the lessons for $3,000.¹⁴

In September 1967, Condon relayed the incident of the Third Universe agent both in an address he delivered to the Atomic Spectroscopy Symposium in Gaithersburg, Maryland, and during an interview with the Rocky Mountain News, the headline of which read “UFO Research Chief at CU Disenchanted,” according to the later article in Look.

“The 21st Century may die laughing when it looks back on many things we have done,” Condon reportedly told the Rocky Mountain News, adding “this [UFO study] may be one.”¹⁵

Shortly before making these comments, Condon had attended a “Ufologist” convention in New York City, a visit that some researchers on the Colorado Project warned against as the convention was associated with fringe, “crackpot” elements of the field, according to the Look article and a later book by Colorado Project principal investigator Dr. David Saunders.¹⁶

Meanwhile, throughout the Colorado Project’s work, Condon found himself managing the fallout of a leaked memo written by Robert Low, Assistant Dean at Colorado University and the Committee’s project coordinator.

The memo, which Low wrote months before the project began, assured university administration against the possibility of identifying “flying saucers.” Low’s apparent bias, and Condon’s defense of Low, reportedly spurred a threat of en masse resignation from project researchers, the definite resignation of three staff members, and the loss of cooperation from the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena. McDonald shared the memo with the press, and Condon and Low allegedly attempted to have McDonald fired from his position at the University of Arizona, according to the article in Look.¹⁷

Condon's Conclusions

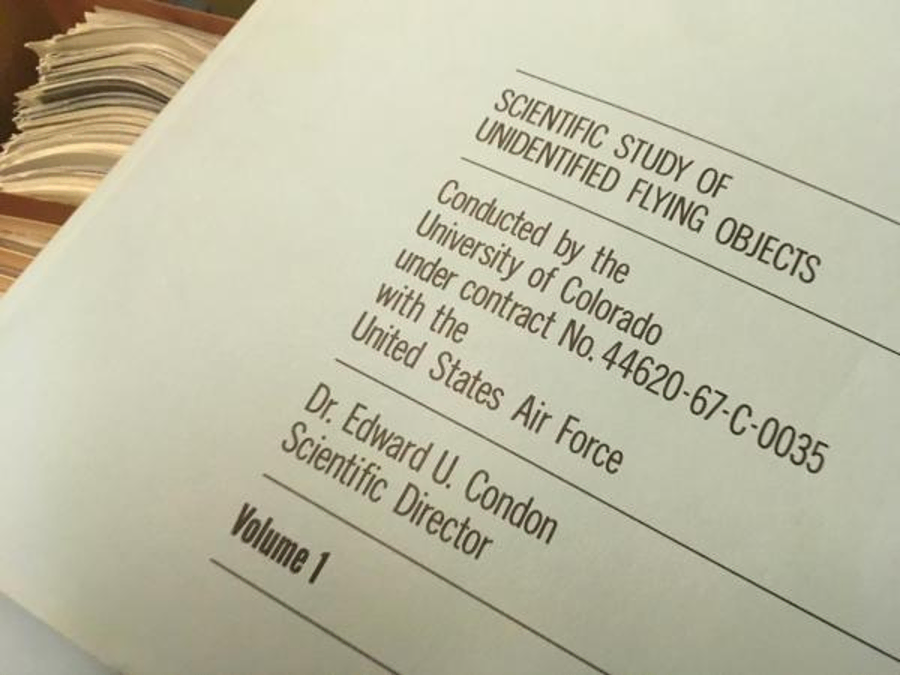

In November 1968, the Colorado Project drew to a close and published its findings in a 1,439-page final report titled Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects, for which Condon wrote summary and conclusion sections.

Condon went over a brief history of the UAP phenomena, the origin of the project, a definition of terms, the research plan, and his skepticism of the “extraterrestrial hypothesis” that alien beings were manipulating the UAPs. After reviewing the immense distances of cosmic space, Condon said, “In view of the foregoing, we consider that it is safe to assume that no ILE,” meaning intelligent life elsewhere, “has any possibility of visiting Earth in the next 10,000 years.”¹⁸

Condon’s “Conclusions and Recommendations” were similarly negative on the prospects of further study into the UAP phenomena. The project did not reveal any “fruitful lines of advance from the study of UFO reports,” Condon said, adding that the field as a general matter of scientific inquiry should not be supported.

Despite persistent criticism that his conclusion stands at a disconnect from certain findings in the report, Condon’s remarks are commonly credited as producing a drop in interest in the UAP phenomenon.

'A waste of government money'

A year after the release of the report, Condon wrote UFOs I Have Loved and Lost, a brief essay of his experience with the Colorado Project. In the essay, which was published by the American Philosophical Society, Condon begins by drawing a connection between the origin of the word spectre, meaning a ghostly, airborne apparition, and spectrum, the phenomenon of light and color.¹⁹

Condon wrote that he was among the few to have written on “spectrology in both of these two distinct meanings.”

Condon goes to illustrate a connection between UAP’s and flights of imagination with two cases, neither of which made it into the Colorado Project’s final report. First, Condon humorously lays out the visit of the Third Universe agent. Next, Condon relates a similarly strange, if more macabre, incident:

According to Condon, the project received a report where a “flying-saucer cult” took the corpse of a young Air Force pilot’s wife and stored it in a barn for three weeks. The cult allegedly told police her soul had traveled to Venus in a UFO and would soon return to recoup its earthly form.

Concluding the essay, Condon wrote that publishers and teachers attempting to convince children that “any of the pseudo sciences” — presumably a reference to the extraterrestrial or ILE hypothesis of UAP research — are “established truth should … be publicly horsewhipped.”

“Truth and children’s minds are too precious for us to allow them to be abused by charlatans,” he said.

Shortly before his death in 1974, Condon repeated to the New York Times his low opinion on the prospects of the scientific study of UAP. “I think further study of UFOs would be useless. I think my own study of UFOs was a waste of government money,” he said.²⁰

Throughout his life, Condon was remembered for the balance of his brilliance and his frank, comical sensibility, qualities that his collaborator the physicist Dr. Philip Morse called Condon’s “proletarian outlook” and “rough-edged kindness.”