Summary

In 1953, a team of researchers finished a statistical analysis of 3,201 UAP reports from the files of the U.S. Air Force’s Aerial Phenomenon Group, which went by the codename Project Blue Book.¹ The analysis remains among the largest studies of its kind and represents the height of the U.S. Air Force’s effort to investigate the post-WWII “UFO” mystery.

This heightened effort, led largely by U.S. Air Force Captain Edward J. Ruppelt, began shortly before a major sighting wave and ended after the so-called Robertson Panel, a four-day, CIA-convened review of UAP evidence by several prominent scientists. The panel strongly recommended the Air Force against pursuing the mystery any further. ²

In May 1955, after a delay of over two years, the Air Force released a version of the statistical analysis in “Blue Book Special Report No. 14.”

The analysis showed that despite best efforts, one out of five Blue Book cases remained unexplained. However, the report found it “highly improbable” that the unexplained cases were evidence of technology beyond contemporary capabilities.

During the gap between the completion and the release of the study, the Air Force reassigned Ruppelt and ended Blue Book’s investigative efforts.

Contract with Battelle

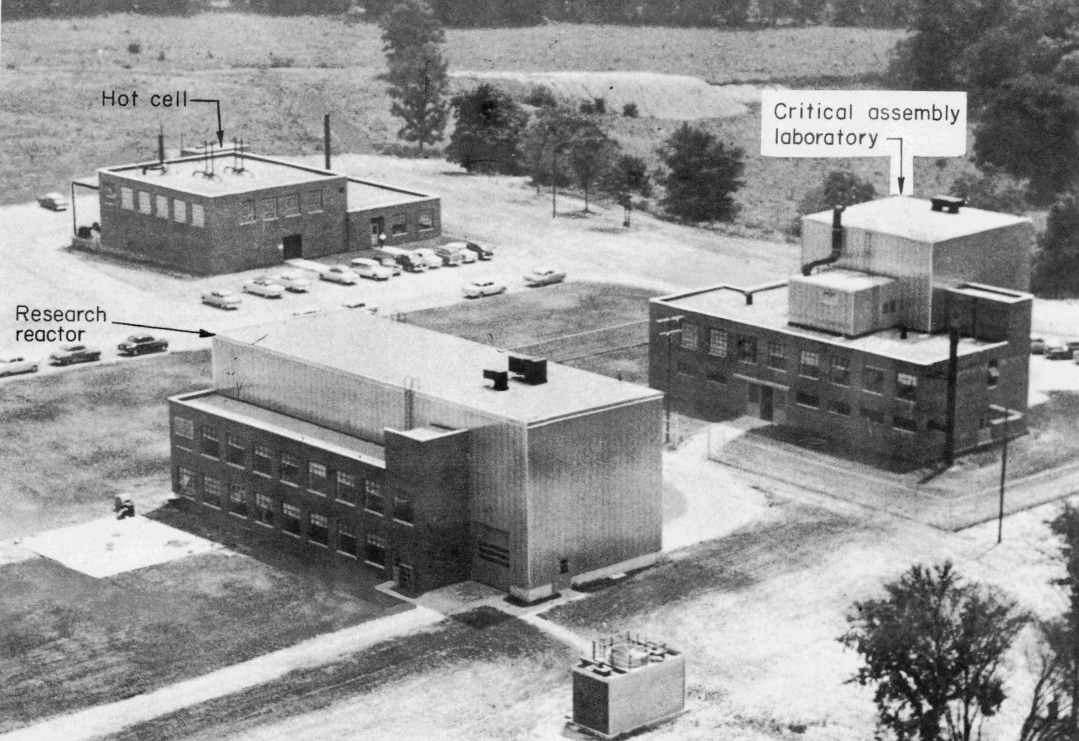

In December 1951, Ruppelt, an Air Force intelligence officer, visited the Battelle Memorial Institute, a science and technology research non-profit in Columbus, Ohio. Ruppelt, who was three months on the job as the director of the U.S. Air Force’s investigative efforts into UAP, had recently gotten approval for a large-scale statistical analysis of the Air Force’s UAP reports. The approval stipulated that he contract the job to a civilian organization.³

Battelle took on the contract, guaranteeing Ruppelt that it would devote statisticians, astronomers, engineers, physicists and psychologists to the analysis. Battelle also proposed developing a standardized reporting form that could be memorialized on IBM punch cards, thereby creating a database that was searchable through an index of a few dozen sighting characteristics.

Three weeks later, Battelle personnel traveled with Ruppelt to investigate a sighting near Minneapolis in order to get a handle on the nature of UAP reports, and soon after, the analysis that would become Project Blue Book Special Report No. 14 got underway.

The analysis, however, had a pair of ill-fated predecessors.

Sign and Grudge

By 1951, Air Force intelligence had twice tackled the UAP mystery. The first effort was Project Sign, and the second was Project Grudge. Both Sign and Grudge produced reports that attempted first to evaluate UAP as a weapons threat, and second to reduce public speculation around UAP.

In both regards, Sign and Grudge faired poorly.

Sign

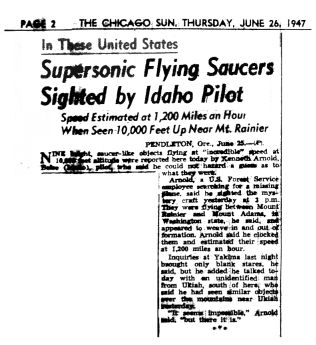

In the spring of 1947, reports of strange aerial phenomena began to trickle in from around the U.S. to the Air Force intelligence office, the Air Materiel Command (AMC) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. The reports described glowing orbs, cylinders, and discs, at turns hovering and speeding across the sky. In June, the reports spiked: 47 in a few weeks.⁴ On the 24th of that month, a civilian pilot named Kenneth Arnold allegedly spotted nine of disc-shaped variety over Mount Rainier, Washington. The press reported “Flying Saucers,” and the name stuck. America’s post-war UFO craze had begun.

On January 7, 1948, the craze became deadly serious when Captain Thomas Mantell, a pilot with the Kentucky National Guard, fatally crashed a fighter plane after chasing a strange, metallic object upward into the sky. ⁵

Two weeks later, the Air Force created Project Sign, an intelligence effort to determine whether UAP were an aerial threat from the U.S.S.R. or another hostile party. In February 1949, after digging into 273 reported sightings, Sign issued its report.

As to whether UAP were Soviet weapons, Sign was unsure. However, the report said, 20 percent of the 273 UAP sightings remained unidentified after analysis, meaning that they were not readily attributable to misidentification of natural phenomena, known technology, psychosis or hoax. ⁶

In an effort to quell public speculation around UAP, the Air Force gave journalist Sidney Shallett for the Saturday Evening Post access to Sign personnel and high ranking Air Force officers. While Shallett’s April and May 1949 two-part feature, “What You Can Believe About Flying Saucers,” concluded that UAP were nothing more “atomic psychosis,” a form of Cold-War mass hysteria, the article had confirmed Air Force interest in UAP.⁷ A record wave of civilian reports of UAP incidents to the Air Force ensued.⁸ ⁹

Grudge

Behind the scenes, the Air Force revived Sign, renaming it “Project Grudge.” Grudge called on analysts from the Rand Corporation, the U.S.A.F.’s Aero Medical Laboratory and Dr. J. Allen Hynek, the head of the astronomy department at Ohio State University, to examine another 226 recently reported UAP incidents.

On December 27, 1949, the Air Force released Grudge’s findings to the press. Once again, the residual of unidentified flying objects remained high at one in five of studied cases. Nevertheless, the Air Force again characterized UAP as misidentification coupled with a “mild form of mass hysteria and war nerves.”¹⁰

Publicly, the Air Force shut down Grudge. The project, however, continued on in a secret and radically diminished capacity, that is until a sighting compelled the Air Force to reopen its investigation.¹¹

Opening Blue Book

Response to Monmouth

On September 10, 1951, an unidentified object flying at over 700 miles per hour appeared on the radar at the U.S. Army base at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Within 15 minutes, two jet pilots in the air nearby spotted beneath a strange silver object of approximately 50 feet in diameter. Allegedly, the object then sped out over the ocean at an estimated 1000 miles per hour. On the following day, the object seemed to reappear on Fort Monmouth’s radar.¹²

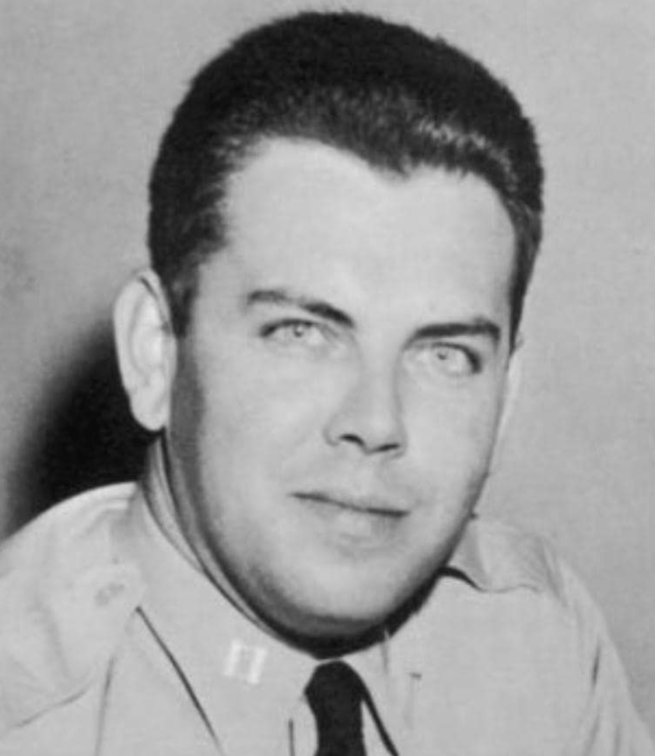

Shortly after the Monmouth incident, the Air Force’s intelligence office, the Air Technical Intelligence Center (ATIC), successor to the AMC at Wright-Patterson A.F.B., assigned Captain Edward J. Ruppelt, an aeronautical engineer and WWII Pacific-theater bombadier, to revive Project Grudge. ¹³

Ruppelt immediately went through the Sign and Grudge files, brought on more personnel, ordered monthly reports, and got a compulsory UAP reporting policy instituted across the Air Force. He also contracted with both the physicist Joseph Kaplan to develop a telescope camera to detect UAP and with the Cambridge Research Laboratory for a similar device that worked by sound.¹⁴

Most notably, as mentioned before, Ruppelt engaged the Battelle Memorial Institute for a statistical analysis of UAP sightings.

In March 1952, ATIC rechristened Grudge as Project Blue Book, officially the Aerial Phenomenon Group. Neither Ruppelt, Battelle, or Blue Book’s personnel could anticipate the meteoric rise of their dataset.

The 1952 Wave

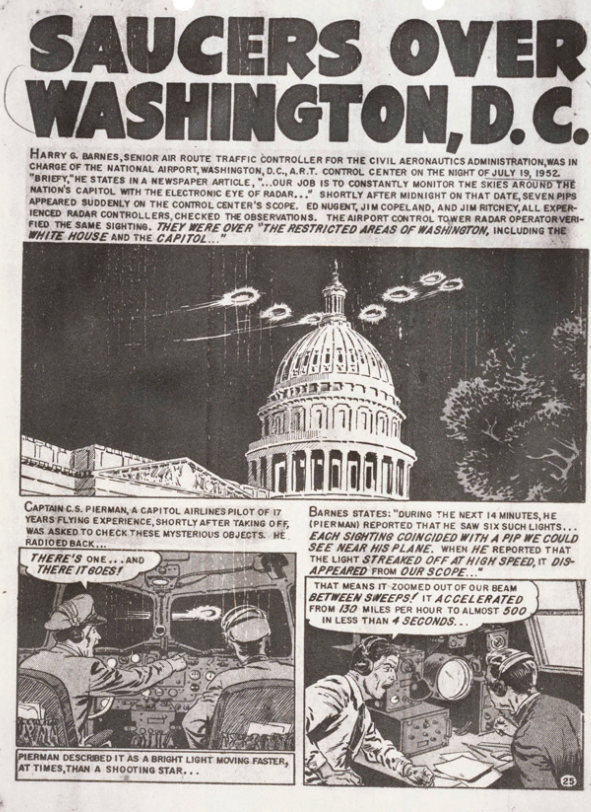

Just before midnight on July 19, 1952, radar at the Washington National Airport caught readings of seven UAP near Washington D.C. Air traffic control radioed Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, advising that the UAP were headed south their way. According to an account of the night from Ruppelt, radar at Andrews clocked one of the objects at 7,000 miles per hour. Within the next few hours, the UAP would allegedly criss-cross the D.C. area. Onlookers from the ground and several pilots in commercial planes would report the bright objects maneuvering in the restricted airspace over the Capitol Building and the White House. At one point, tower operators at Andrews reportedly saw a “huge fiery-orange sphere” hovering over them. ¹⁵

In the following week, similar reports with visual and radar confirmation of UAP occurred from Virginia to New Jersey. On July 26, UAP reappeared on radar covering Washington D.C. The Air National Guard at New Castle, Delaware, scrambled jets. The pilots made visual contact, the UAP reportedly disappeared, and when the pilots turned back for base, the UAP allegedly returned.¹⁶

Already, UAP sightings were on the rise. In June 1952, Blue Book had received 149 reports, a record high. In July, the tally went up to 536. By the end of the year, Blue Book received 1,501 UAP sighting reports.¹⁷

The volume of reports contributed to an attitudinal shift of one of Blue Book’s key contributors: the astronomer Dr. J. Allen Hynek.

Hynek’s address

In October 1952, Hynek traveled to Boston, Massachusetts to a gathering of the American Optical Society. At that point, Hynek had been a civilian scientific consultant to the Air Force for four years, first under Project Grudge and now Blue Book. In the early days, his job, as he and his superiors understood it, was to go through the reports, pick out where someone had confused Venus, for example, with a flying saucer, and in this manner consign the vast majority of cases to witness error. ¹⁸

Those “most weird reports” that he could not “demolish by explanation” he’d dismiss as cases for the “psychologists,” he said.¹⁹

Recently, though, he’d begun to think differently of the whole enterprise, he said. Within the recent volume of cases, certain patterns had become undeniable.

Hundreds of witnesses had alleged that lighted objects in the sky were hovering, creeping, reversing directions, turning at sharp angles, changing from one color to the next and disappearing at impossible speeds, Hynek said. Altogether, these “nocturnal meandering lights” did not fit the description of any natural phenomena or known technology, and the witnesses were not unreliable or stupid. They weren’t “intellectual flyweights” and “bird brains.” They were often pilots and radar technicians, he said, and as a rule were not seeking publicity.²⁰

To date, Hynek said, the scientific community had met these reports as he once did, with dismissal and ridicule. Hynek urged his audience to open their minds and engage the unexplained phenomena as an opportunity for science. “Ridicule is not part of the scientific method,” he said, “and the public should not be taught that it is.”²¹

A few months later, Hynek and Ruppelt would make a similar case to a panel of scientists secretly convened in Washington D.C.

The panel would remain unconvinced.

The Robertson Panel

The meeting

On January 14 through 18, 1953, a panel of distinguished scientists with military experience secretly convened in Washington D.C. at the request of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to review evidence from Blue Book and determine whether UAP posed a security threat. The panel was led by Dr. Howard page Robertson, mathematician and astronomer, and included Drs. Thorton Page, physicist and astronomer, Samuel Goudsmit, Luis Alvarez, both physicists, and Lloyd Berkner, physicist and radar expert.

Ruppelt briefed the panel on Blue Book investigations and presented footage of alleged UAP filmed by Navy photographers that underwent as much as 1,000 hours of frame-by-frame analysis.²²

Hynek presented evidence from the yet-incomplete Battelle analysis, referred to as “Project Stork” in the panel’s minutes.²³ Reportedly, Battelle analysts had requested a month earlier that their study not be presented as methodological problems remained, and Batelle further urged that sounder conclusions would result from an experimental study that compared observations from specified areas of sky.²⁴ Hynek, who was an associate member of the panel, also presented a plan similar to Battelle’s proposal, arguing that cameras, under development by the physicist Joseph Kalplan, could, if affixed to six specific observatories, provide a nationwide visual UAP detection mechanism.

Major Dewey Fournet, an aeronautical engineer and the Pentagon’s liaison officer to Blue Book, presented further evidence and argued that maneuvers observed by UAP indicated intelligent control. Fournet argued, by process of elimination, that the intelligence could be extraterrestrial.²⁵ Finally, Brigadier General William Garland, chief of the Air Technical Intelligence Center, argued that UAP investigations should be declassified and that Blue Book should continue on with a substantially larger staff.²⁶

Conclusions, standard of evidence

All together, over the course of 12 hours, the panel reviewed eight UAP incidents in detail and discussed 15 cases in more general terms. From this study the panel concluded that no direct evidence demonstrated that UAP were a threat to U.S. security.

In reaching its conclusion, the panel had applied a strict standard of evidence. The existence of truly unexplainable aerial phenomena would require a fundamental revision of scientific concepts, the panel said. So, to assert that UAP are genuine, rather than misidentifications and hoaxes, required evidence of the highest order, they said.

“A new phenomenon, to be accepted,” the panel said, “must be completely and convincingly documented. In other words, the burden of proof is on the sighter, not the explainer.”²⁷

Ruppelt later described the panel’s approach as a search for “loopholes” in all evidence presented. “Scientific evaluation has no room for even the smallest of loopholes,” he said, “and we had asked for a scientific evaluation.”²⁸

Ruppelt, however, did not see the panel’s report and was under the impression that they ultimately encouraged further investigation of UAP.²⁹ According to UAP historian Dr. David Jacobs, based on a review of Ruppelt’s correspondence, CIA agents directly told both Rupplet and Garland that Blue Book would go on with more staff and less secrecy.³⁰

The panel, in fact, had proposed the opposite.

Recommendations

While UAP did not constitute a direct threat, widespread public speculation over UAP posed a serious danger to the U.S., the panel had said.

“Mass hysteria” surrounding UAP craze was overloading “emergency reporting channels with ‘false’ information,” and leaving the country at a “greater vulnerability to possible enemy psychological warfare,” the panel said.³¹

Following from this conclusion, the panel recommended that anyone taking on the work of handling UAP reports ought adopt a “debunking” stance rather than an investigative approach. To encourage curiosity around UAP invites the further “clogging up of channels of communication by irrelevant reports” and a “threat to the orderly functioning of the protective organs of the body politic,” the panel said.³²

To reduce public interest in UAP, the government should carry out “public education” through “mass media,” such as television, movies and magazine articles, to dispel the UAP mystery.³³

“The use of ‘true’ cases, first showing the ‘mystery’ and then the ‘explanation’ would be forceful,” the panel said. The panel suggested that the CIA enlist the help of experts in mass psychology to create content of maximum effect.³⁴

Finally, the panel recommended that the CIA closely monitor civilian UAP investigation groups, specifically the Aerial Phenomenon Research Organization, or APRO, and the Civilian Flying Saucer Investigators.

“The apparent irresponsibility and the possible use of such groups for subversive purposes should be kept in mind,” the panel said.³⁵

Fallout

In 1953, following the Robertson Panel and its recommendations, the Air Force performed an about-face with regard to investigating UAP.

In February 1953, The Air Force issued Regulation 200-2, which said that airmen may only respond to local inquiries on UAP incidents when Air Force intelligence has positively identified the alleged UAP as “as a familiar object.”³⁶

That same month, Ruppelt was temporarily reassigned away from Blue Book. When he returned in July 1953, he found that his staff was gone save for two assistants. Additionally, higher-ups had rejected plans for UAP detection devices from Kaplan and the Cambridge Research Laboratory.³⁷ Ruppelt looked over the new reports, but the wave that had characterized 1952 was over. In July 1953, Blue Book fielded only 21 UAP sightings.³⁸ More importantly, according to Ruppelt, a commanding officer, General Woodbury M. Burgess, told him that while Blue Book could receive reports, it could no longer investigate. From now on, investigations would go to the newly operational “Air Intelligence Service Squadron” out of Colorado.³⁹ In the following month, Ruppelt left Blue Book.

In December, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff further tightened the flow of UAP information. In a publication to the Army, Navy and Air Force, the Joint Chiefs of Staff said that any military personnel or civilian who releases classified UAP information was liable under the Espionage Act for a year in prison and a $10,000 fine.⁴⁰

Meanwhile, Battelle had finished its analysis of 3,201 Blue Book cases.

Special Report No. 14

Though the Battelle analysis wrapped in 1953, its findings were not circulated to Blue Book that year. Eventually the report came out internally in May 1955 as Blue Book Special Report No. 14, which was made public in the following October.⁴¹

As with the reports from Sign and Grudge, the Battelle analysis found that a substantial number of UAP incidents resisted explanation as either misidentification of natural phenomena or known technology, or as products of hoax or psychological delusion.

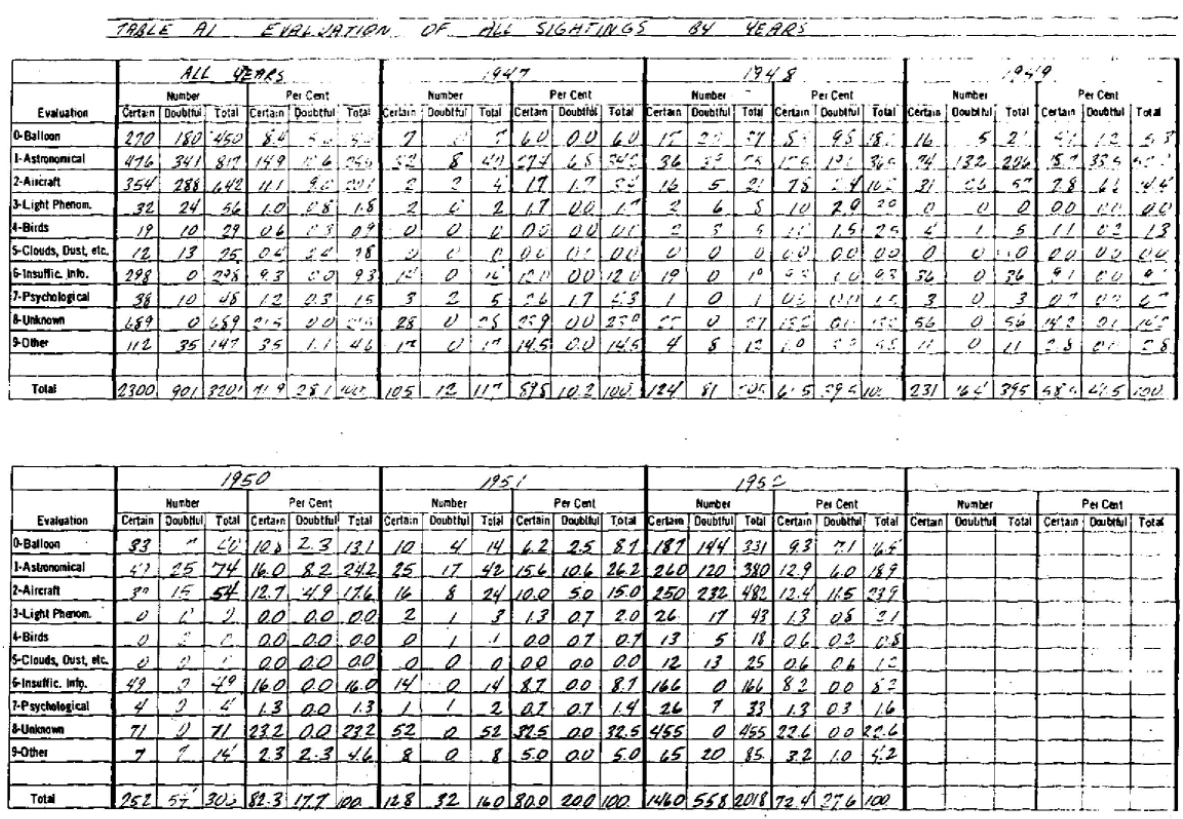

The analysts deemed these cases “unknown.” They represented 21.5 percent of the cases studied.⁴²

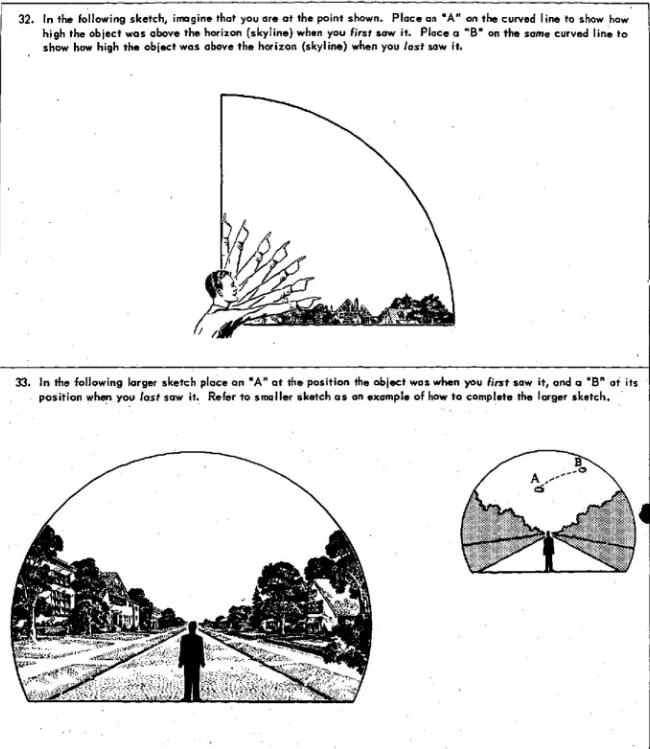

From an initial dataset of roughly 4,000 cases, Batelle converted 3,201 cases into IBM punch cards that memorialized 33 characteristics, such as color, brightness, number of UAP, shape, duration of sighting and speed.⁴³ Analysts developed ratings for witness credibility, taking into account occupation, training, consistency and thoroughness of details, and “attitude.”⁴⁴ Each UAP incident was available for study from four analysts. If the first two analysts on a case agreed on a prosaic explanation, such as misidentification of clouds or seagulls, the sighting was deemed solved.

“Unknown” cases, however, came with a higher standard and required agreement from four analysts, two from Battelle, and two from the Air Technical Intelligence Center.

In determining cases, analysts rated their decisions as either “certain” or “doubtful.” Just over half of the solved cases were “certain,” and about thirty percent were “doubtful.” In contrast, 100 percent of the “unknown” cases were rated “certain.”

Solved cases represented 69.2 percent of the 3,201 cases, with misidentification of astronomical phenomenon and aircraft as the leading culprits, and 9.3 percent of cases presented insufficient evidence for determination. Of the 3,201 cases, only 48, or 1.5 percent, were deemed to be the result of delusion or hoax.

The vast majority of cases, the report said, came from “serious people, mystified by what they had seen and motivated by patriotic responsibility.”

As for a conclusion, Special Report No. 14 echoed Sign, Grudge and the Robertson Panel, finding that UAP were likely not signs of unknown technology.

“It is considered highly improbable,” the report said, “that reports of unidentified aerial objects represent observations of technological developments outside the range of present day scientific knowledge.”

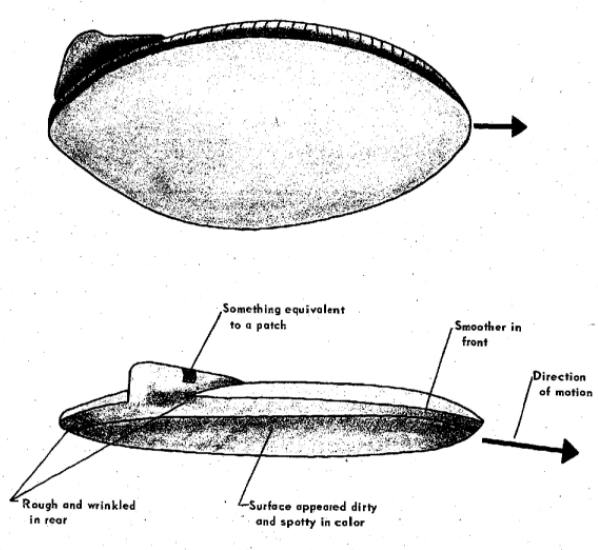

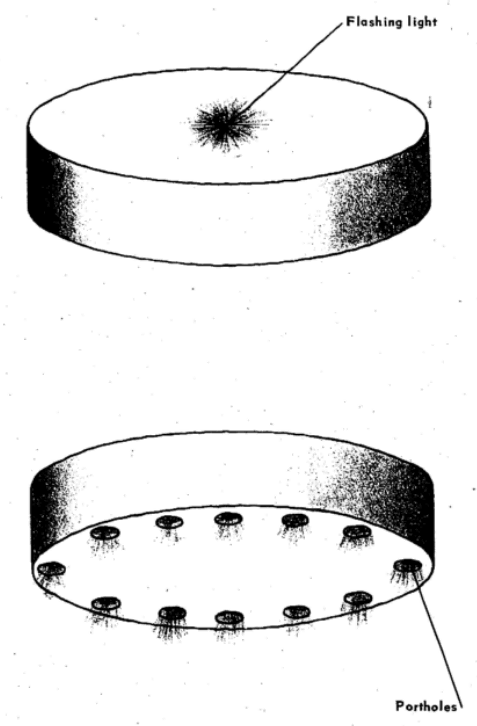

(Illustration of an alleged UAP from Blue Book Special Report “Case XI”)

Special Report No. 14 runs 316 pages and contains dozens of graphs and hundreds of data tables. Throughout, the report makes note that all sightings are eyewitness accounts and less than ideal with regard to establishing the physical nature of the phenomenon. “It must be emphasized, again and again,” the report said, “that any conclusions contained in this report are based NOT on facts, but on what many observers thought and estimated the true facts to be.”

The delayed report, which captured data from the 1952 wave, represented the height of the Air Force’s investigation into UAP. More than a decade would pass before anyone would carry out a UAP study of like ambition.