Summary

The National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena, or NICAP, was a private UAP research and education network in the United States that exercised considerable lobbying power from the late-1950’s through the 1960’s. NICAP not only coordinated investigations of UAP around the US, but sought to move the US government toward an open and vigorous effort to discover what was behind “flying saucers.” Largely animated by its director, Donald E. Keyhoe, NICAP partly achieved this goal with the 1966 creation of the Condon Committee, a public-facing, government-backed UAP research project. However, the Condon Committee’s ultimately negative conclusion on the worth of UAP deflated NICAP’s membership roles and its clout among Washington DC’s scientific, military and political establishment. Further weakened by administrative missteps, NICAP’s influence waned until it finally closed in 1980.

Born in DC

Initially known as “Project Skylight,” NICAP began in 1956 as a private UAP investigation group headquartered in Washington DC at 1536 Connecticut Ave NW. Founder and director Dr. T. Townsend Browne, an inventor, scientist and U.S. Navy veteran, described the group to The Washington Daily News on Oct. 29, 1956, as “seventy-five scientists, educators and church leaders” interested in “flying saucers,” a term that, Brown admitted, made him “wince.”

Brown envisioned NICAP as a “fact-finding body serving the national public interest” supported by dues-paying members across the country.¹

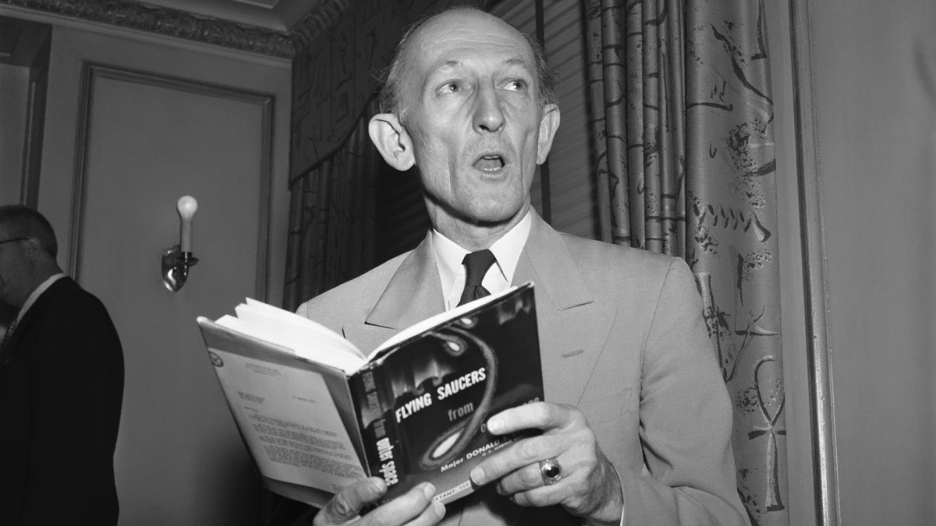

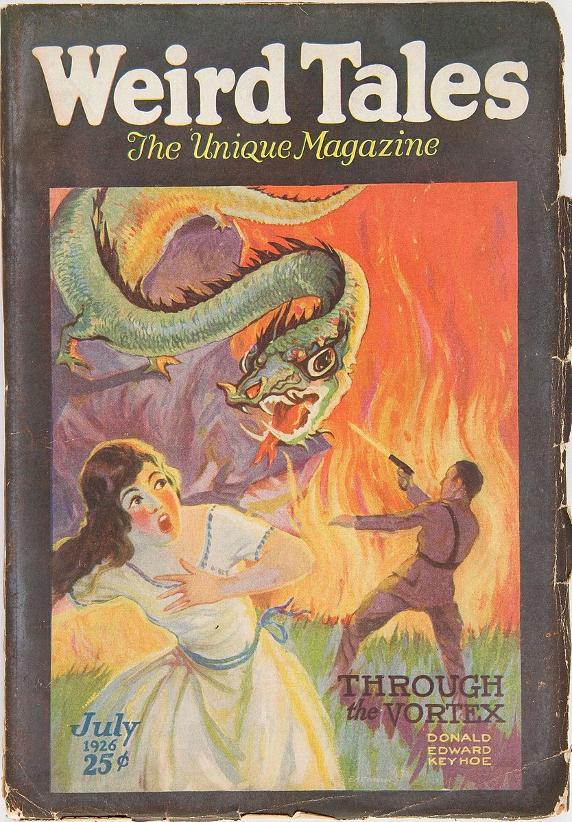

Brown’s tenure as director lasted but a few months. According to author James W. Moseley, NICAP’s board of governors forced Brown to resign for directing NICAP-funds towards his own research into an anti-gravity engine. Major Donald E. Keyhoe, U.S. Marine Corp, retired, who allegedly led the charge against Brown, was appointed as NICAP’s director.² ³

Keyhoe shared Brown’s vision of a investigative network that would, Keyhoe said, “expose hoaxes and ferret out the facts,” but he also saw NICAP as a lobbying group, and to that end he doggedly recruited powerful names to NICAP’s roster; its Board of Governors soon featured several names the Washington DC scientific and military elite.⁴ The aim of NICAP’s lobbying was largely to end government censorship that had, Keyhoe said, “muzzled hundreds of pilots” and other witnesses.⁵

Among NICAP earliest acts under Keyhoe was a January 1957 press conference called by NICAP member Rear Admiral Delmar S. Fahrnery, former head of the U.S. Navy’s guided missile program. Fahrney delivered a three-part message that would serve as an illustration of NICAP principles for years to come: UAP were indeed appearing in the skies, Fahrney said; they were directed by some kind of “intelligence,” and the US Government, particularly the Air Force, had to simultaneously ramp up and open up its investigation of the phenomena, he said.⁶

NICAP’s press savvy declarations, backed by widely respected names such as Fahrney and Roscoe Hillenkoetter, NICAP board member and former (and first) director of the Central Intelligence Agency,⁷ drew new members to NICAP’s quickly expanding investigation network. By 1960, NICAP claimed thousands of members across the US, including 200 trained investigators.⁸

Targeting Intelligence

To shed daylight on government investigations into UAP, NICAP and Keyhoe focused effort on US military and intelligence agencies.

Keyhoe urged, for example, the CIA to reveal the findings of the “Robertson Panel,” a secret, CIA-sponsored panel of civilian scientists charged with performing a threat assessment of UFO data that met for a total of twelve hours between late-1952 and early-1953.⁹ After private correspondence with the CIA failed to win release of the information,¹⁰ Keyhoe revealed the group on a March 1958 episode of The Mike Wallace Interview (an episode during which Keyhoe also spoke at length on an alleged USAF policy to deny its own UAP investigations).¹¹

According to a 1979 New York Times article based on released CIA documents, NICAP’s effort to uncover the Robertson Panel prompted the agency to release a sanitized version of the panel and sparked a long-lived CIA interest in Keyhoe and NICAP.¹²

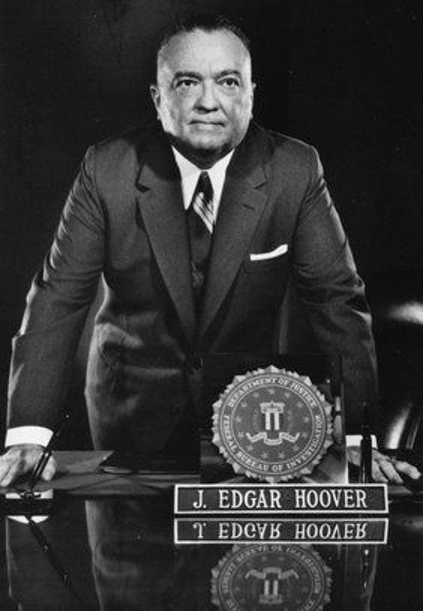

The FBI also had developed an interest in NICAP and Keyhoe, suspecting that Keyhoe had “ulterior motives” in his efforts to bring transparency to the government’s investigation of UAP, according to in-house CIA historian Gerald Haines.

Keyhoe, in his capacity as NICAP director, often corresponded with agency heads. He asked FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover whether the FBI had releasable information on UAP investigations. He also asked whether FBI agents had been told to discourage UAP witnesses from sharing their stories. Hoover responded that the FBI had nothing on UAP and that extraterrestrials were outside of the bureau’s “function.”¹³

An internal FBI memo circulated at the time of Keyhoe and Hoover’s correspondence advising that Keyhoe was “flamboyant” and “irresponsible” and that the Bureau should avoid contact with him.¹⁴

Meanwhile, a steady stream of concerned citizens, some of whom had recently joined NICAP, wrote to the FBI, asking whether NICAP was a communist front. Hoover himself would often respond to the letter writers. Typically, Hoover demurred as to whether NICAP was communist. Meanwhile, he’d enclose pamphlets and comics bearing such titles as “Breaking the Communist Spell” and “The Communists are After our Minds” with his response.¹⁵

At one point in August 1960, U.S. Air Force Colonel Lawrence J. Tacker, a spokesman for the USAF on UAP issues, asked Hoover whether the FBI could shut down NICAP, “a thorn in the side of many government agencies.” The FBI could enforce, Tacker suggested, a recently passed law prohibiting private organizations from trading on the name of the U.S. Government. Hoover responded that the law applied primarily to financial firms.¹⁶

In 1961, the head of the FBI office in New Orleans wrote to Hoover, advising him that a clerk in the office had joined NICAP. Hoover responded that “NICAP is the type of organization the Bureau’s name should not be connected with - either through employee membership … or by any other means.”¹⁷

Moving Congress

Beyond tussling with intelligence agencies through letter, NICAP carried out a public campaign to move the US Congress to action over the UAP phenomena.

In June 1960, NICAP submitted to the U.S. Congress a report arguing that UAP might inadvertently trigger war with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as they might be perceived as Soviet missiles or aircraft. The solution, NICAP argued, was for Congress to drum up government resources to investigate UAP transparently and to open the books of the CIA, FBI, USAF and any other government agencies that had delved into the issue.¹⁸

The report summarized for Congress several alarming UAP reports that the USAF had denied or “written off.” NICAP member Captain Edward J. Ruppelt, USAF retired, former chief of Project Blue Book, a USAF UAP investigation effort, wrote that the USAF policy was to “debunk” UAP reports and “purge” investigators that didn’t go along.¹⁹

NICAP asked Congress to consider that a certain percentage of UAP may be “interplanetary machines.” In support of this possibility, NICAP summarized various startling theories from astronomers on intelligent life in the galaxy, including an assertion from White House scientific advisor S. Fred Singer that the moons of Mars were “artificial satellites launched by an earlier Martian civilization.”²⁰

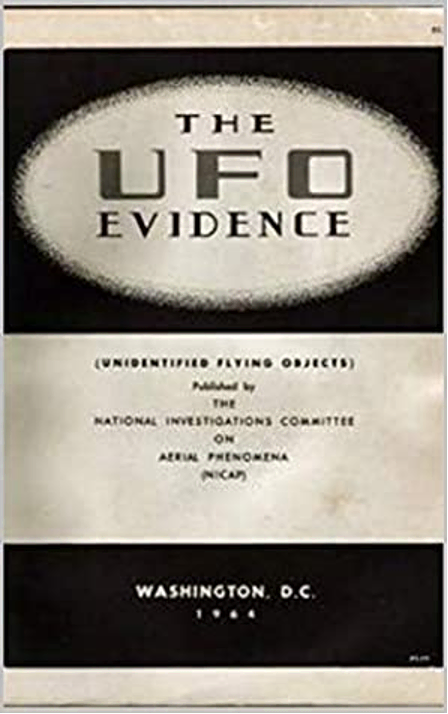

NICAP followed up with 1964’s The UFO Evidence, compiled primarily by Richard Hall, a former Airman with scientific training who came onto NICAP staff in 1957. The UFO Evidence presented facts from 746 of NICAP’s approximately 5,000 UAP reports, favoring those cases with scientists, professional pilots, police officers, USAF personnel as eyewitnesses, to support the conclusion that certain UAP sightings indicate real physical objects that are under the control of living beings.

“This report,” NICAP said in a statement from its Board of Governors, “is an attempt to clarify the reliable evidence of UFOs, and to remove the fog of mysticism and crackpotism which has helped to obscure the real issues.”²¹

Despite its explicitly narrow audience — the US Congress — the book’s sales blew past Hall’s and Keyhoe’s expectations.²

In April 1964, just two months before the book came out, a highly publicized UAP sighting occurred in Socorro, New Mexico, where a police officer allegedly saw two white figures beside a white craft that abruptly shot up from the desert floor into the sky. A rash of sightings ensued across the country, prompting widespread curiosity over UAP. NICAP’s tome, The UFO Evidence, was apparently the most comprehensive and thorough guide available.

Within a few years, NICAP grew to roughly 14,000 members, including 300 investigators trained with some manner of military and scientific training.²³

The wave of reports culminated with highly publicized 1966 sightings in central Michigan, which caught the attention of then U.S. House of Representatives Minority Leader and representative of Michigan’s 5th congressional district Gerald Ford. Ford called for hearings, saying “the American people would feel better if there were a full blown investigation of these incidents.²⁴

On April 5, 1966, the Committee of Armed Forces of the House of Representatives held hearings on the ongoing spate of UAP sightings. Throughout, speakers referred to NICAP and the data it furnished on par with data supplied by the USAF. The chairman of the committee, Representative L. Mendel Rivers of South Carolina, at one point asked for clarification from Dr. J. Allen Hynek, an astrophysicist and consultant to USAF’s Project Blue Book, as to whether NICAP was itself a government agency.²⁵

The Committee of Armed Forces concluded that the USAF had fallen short of adequately investigating the UAP phenomenon. The Committee suggested the USAF partner with universities and non-profit organizations to perform a thorough, public-facing investigation into the UAP mystery.²⁶

NICAP’s nine years of lobbying appeared to have borne fruit.

Success, Failure

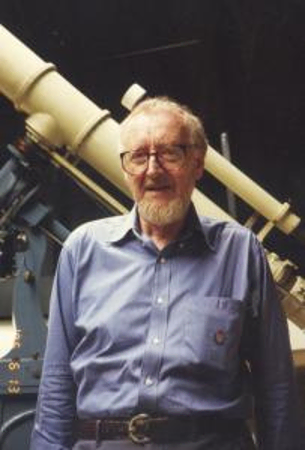

The government-backed, public facing initiative to study UAP took shape at the University of Colorado under the direction of Dr. Edward Condon, a major figure in quantum physics and the study of light. The initiative, which became known variously as the Condon Committee and the Colorado Project, employed a staff of 37 investigators and ran from October 1966 to November 1968.

To aid the Condon Committee, NICAP passed along new UAP reports from its “early warning network.” NICAP, which had long employed only Keyhoe and Hall, expanded to a staff of nine and “leased a Xerox machine” to provide the Condon Committee with copies of strong cases from NICAP’s files, Hall said. The organization “generally threw [itself] wholeheartedly into the campaign,” Hall recalled, claiming that he personally compiled briefings of NICAP’s most inexplicable cases and hand delivered them to Condon.²⁷

NICAP’s relationship with the Condon Committee, however, did not survive the investigation’s two-year lifespan.

In early 1967, a few months into the Condon Committee’s work, a member of the Committee shared with Hall and Keyhoe a memo written by Robert Low, Assistant Dean at Colorado University and the Committee’s project coordinator. The memo assured university administration against the possibility of identifying “flying saucers.”²⁸

According to an article in the May 14, 1968, issue of Look magazine, Low told administrators that the “trick would be [to] appear a totally objective study but, to the scientific community … present the image of a group of nonbelievers trying their best to be objective but having an almost zero expectation of finding a saucer.”²⁹

According to Hall, he and Keyhoe remained optimistic. Low was responding to internal university pressures, they reasoned, and moreover, the strength of NICAP UAP reports would overcome any bias, they hoped. However, as the months wore on, they found themselves more distressed with Condon himself, who according to Hall, evinced a dismissive attitude on the subject both privately and publicly. (In public events and interviews, Condon disparaged the possibility that findings of scientific value could emerge from the Committee, according to Look, which in turn cites articles in The Denver Post, Rocky Mountain News and The Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York. In a private briefing, Hall said, Condon dozed off.)

NICAP continued to refer recent sightings from its newly established “Early Warning” network to the Condon Committee and continued to supply reports from its records, however, in the later months of the Committee’s work, Hall and Keyhoe discovered that none of NICAP’s “strong cases” were investigated as part of the Committee final report.

In May 1968, Keyhoe announced that NICAP was breaking ties with the Condon Committee. In a statement published both in the Washington Evening Star and Look magazine, Keyhoe took particular issue with the fact that Condon himself did not investigate any of the cases.³⁰

In November 1968, the Committee wrapped and soon after released its findings to the public. The Committee prefaced its 1,439-page final report with conclusion and summary sections from Condon in which he wrote that the project did not reveal any “fruitful lines of advance from the study of UFO reports” and that UAP as a general matter did not merit scientific inquiry.³¹

The Condon Committee’s final report substantially chilled interest in UAP, both in NICAP’s target audience of legislators and DC influencers, and the public at large. By the time of the report’s release as a mass market paperback, NICAP had entered a downward spiral.

NICAP’s volunteer and membership numbers dropped precipitously. The board had lost powerful members, such as former-Central Intelligence Director Roscoe Hillenkoetter. Several staff members who were allegedly owed back pay quit. Members of the board reportedly had the lock changed on the office of Gordon Lore, NICAP’s chief researcher.³² The board fired Keyhoe.

What was left of NICAP’s staff, according to Hall, who himself left in July 1969, “drifted toward organizational gridlock and bankruptcy.”

The “real NICAP,” Hall later said, was over.³³

(It should be noted that while the conclusion of the Condon Committee was decisively negative for NICAP’s future, NICAP had long suffered organizational problems. By Hall’s own account, neither he nor Keyhoe had administrative experience and were frequently accused of “unsound practices.”³⁴ NICAP reports to its board of governors, from 1957 into the 1970s, are replete with talk of looming bankruptcy, shortfalls on payroll and the possibility of shutting down.³⁵ Even in its best years, NICAP was unable to handle the volume of work — correspondence, investigation, training, publishing — that it set for itself. In 1967, for instance, when NICAP estimated 10,000 dues paying members, it expected its costs would double its income.)³⁶

Decline, Alleged 'Infiltration'

NICAP persisted for another decade, though little information is available on these latter years. Lore and Hall provided brief accounts of NICAP’s final years, however, Lore and Hall had little contact with the organization during that time and had parted from NICAP with some grievances. Lore stated in 2018, online and in his book Flying Saucers From Beyond the Earth, that he believed NICAP’s decline was in part a result of CIA infiltration.³⁷ In personal recollections from 1994, Hall entertains, but does explicitly endorse the CIA “mole” theory.³⁸

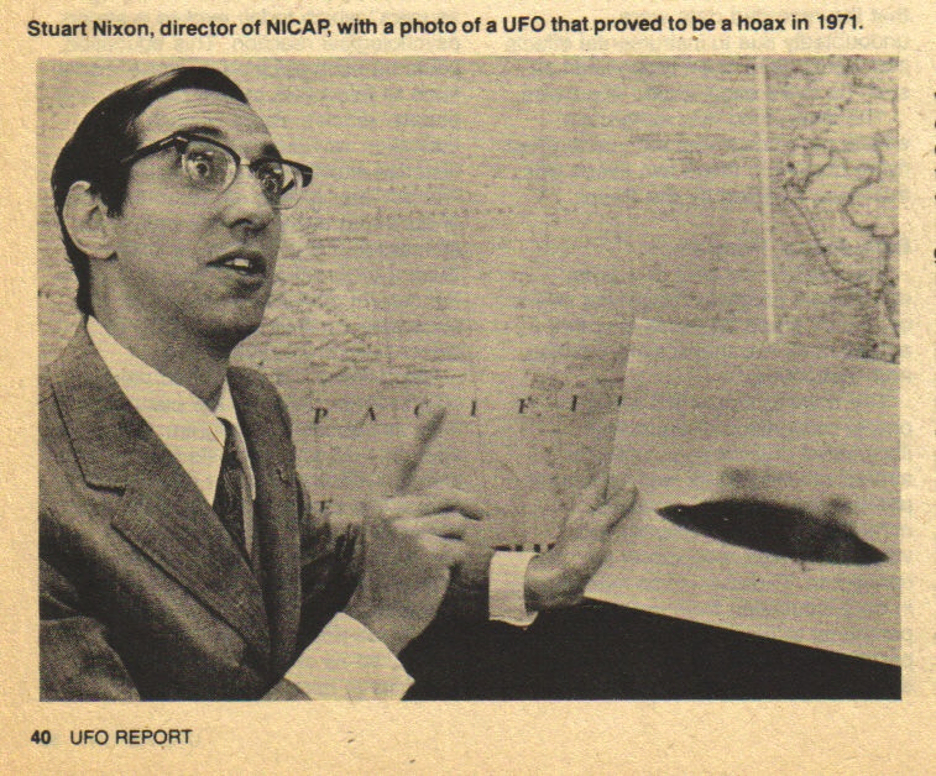

Both Hall and Lore alleged that John Acuff and G. Stuart Nixon, who filled the leadership vacuum and served as NICAP directors in the 1970s, were CIA agents or were connected to the CIA. However, a contemporaneous CIA document on NICAP (released in 2010) makes no mention of an affiliation between Nixon and the agency.³⁹

At the outset of the 1970’s, Count Nicolas de Rochefort, a psychological warfare expert and analyst at the Library of Congress⁴⁰ served on the board, as did Colonel Joseph Bryan III, USAF retired, an ex-CIA agent, according The New York Times.⁴¹

(Joseph Bryan’s son, journalist C.D.B. Bryan, wrote in his book Close Encounters of the Fourth Kind that his father’s CIA affiliation was not connected to NICAP’s decline. “Anyone who knows anything about the history of NICAP knows that the group didn’t need anybody's help in its disintegration; it simply self-destructed," C.D.B. Bryan wrote.⁴²)

Charles Lombard, confirmed ex-CIA agent and aide to former senator and Republican-party presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, joined the board in 1971.⁴³ (Goldwater himself joined the board in 1974).⁴⁴

Succeeding Nixon in 1978, Alan Hall (no relation to Richard Hall) took over as NICAP director. According to the New York Times, Alan Hall was an ex-CIA with a 30-year tenure in the agency.⁴⁵

In a deal partly brokered by Richard Hall and Dr. J. Allen Hynek, NICAP sold its files to Hynek’s organization, the Center for UFO Studies in 1980. NICAP closed that same year.